WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump’s executive order singling out transgender service members wasn’t a shock to Lt. Cmdr. Geirid Morgan and her family. Nor was the Pentagon’s accompanying policy to remove trans troops from the force, released about a month after Trump’s order.

“The first feelings I had really were just, concerned for my fellow transgender service members, concerned for their families, concerned for the service members that service under them,” she said.

Morgan has spent 14 years moving up the ranks in the U.S. Navy. Long-serving trans service members, like Morgan, are now plaintiffs in legal challenges against Trump’s ban. To the trans troops suing the government — among them, an Air Force staff sergeant with 16 years of service, a Navy commander with 19, an Army sergeant first class with 20 — the ban is poised not only to harm them, but also drain experience and expertise from the military.

Trump’s latest attempt at a trans military ban has been in court this week. A federal judge ruled Tuesday that the ban was likely unconstitutional and “soaked in animus” and could not move forward. The government responded Friday asking the judge to dissolve the injunction before it goes into effect.

Earlier in the week, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth wrote on X that “we are appealing this decision, and we will win.”

Trans service members who spoke with PBS News days before the judge’s ruling, and shared their views in a personal capacity and not on behalf of the Defense Department, said they worry about the uncertainty of what’s next.

“I hope there isn’t a perception from anyone that we’re going to be voluntarily separated from service and then sort of just go on and live our best lives right now, because that’s becoming more and more difficult for a trans person in America,” Morgan said.

Morgan with her wife, Christina, and dog, Kara, at their home. Photo by Tim McPhillips/PBS News

Trump made targeting trans people one of the cornerstones of his re-election campaign, crescendoing to a multi-million dollar campaign ad blitz weeks before November’s vote. There were ads with anti-trans rhetoric against a group of people that makes up less than 1 percent of the U.S. population.

In remarks from the Oval Office last week, Trump said he told Republicans to focus on trans rights in the ramp-up to Election Day.

“I said, ‘Don’t bring that subject up because there is no election right now. But about a week before the election, bring it up,’” he said.

A majority of Americans — 58 percent — favor trans people openly serving the military, according to a Gallup poll conducted in January as Trump began his second term. But that support has fallen in recent years. In 2019, 71 percent of Americans supported trans troops. The decline is largely driven by Republicans, the poll found. Some seven in 10 Republicans now oppose the idea.

Against that backdrop, Trump picked Hegseth, who once said being trans “creates complications and differences” in the military, to lead the Defense Department. Once confirmed, the former Fox News Channel host put the president’s “anti-woke” agenda at the center of his reorganization of the armed forces.

Pointing to Trump’s 2017 attempt to ban trans troops from the military, Morgan’s wife, Christina, said they’d hoped the new effort, “was ‘talk’ and not ‘do’ because that happened a lot in the first administration.” But what was surprising this time was the language, she said, “how insulting it was.”

The 1,000-word executive order Trump issued in January never uses the word “transgender,” which means having a gender identity that differs from the sex one was assigned at birth. It used specific framing to argue that the country’s military has been “afflicted with radical gender ideology.”

Civil rights and LGBTQ+ advocacy groups have rebuked the ban in court, saying it violates trans people’s equal protection rights under the Fifth Amendment.

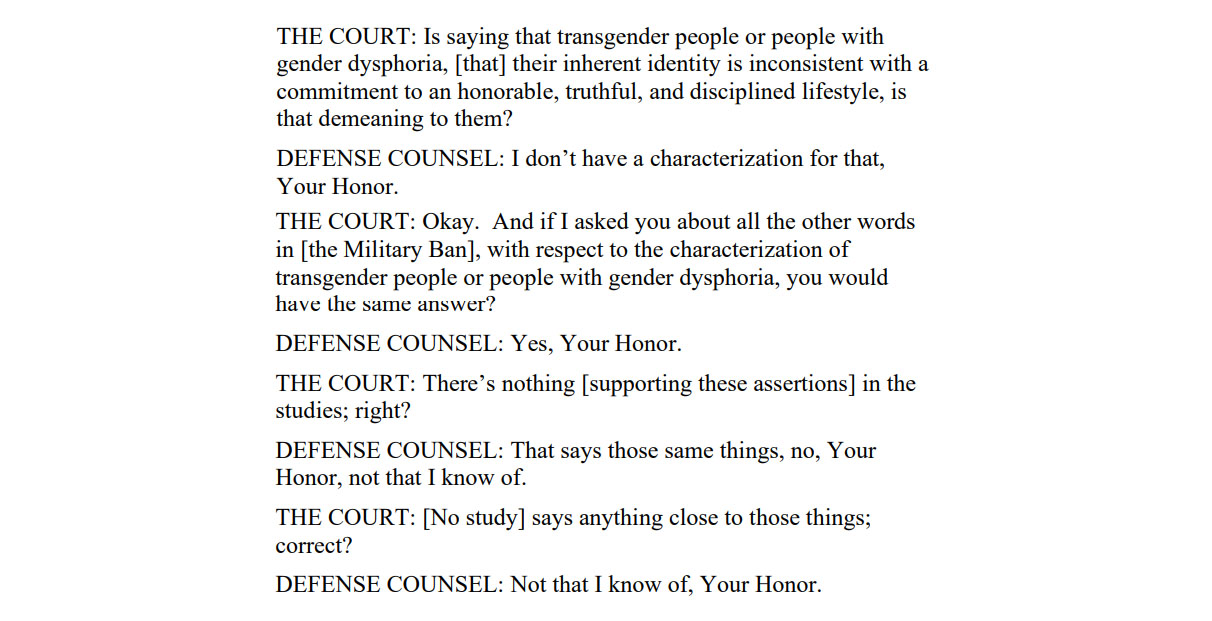

The language in the Trump administration’s policy rollout also demeans trans people as “dishonest and selfish and undisciplined,” said Jennifer Levi, senior director of transgender and queer rights at GLAD Law.

“It’s a character assassination based on nothing,” said Levi, who’s a lead attorney in the case that received the nationwide preliminary injunction. “And animus alone can never justify targeting a group and punishing them without justification other than hostility.”

In his executive order, the president suggested that being trans and a soldier were incompatible, that being trans “conflicts with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful, and disciplined lifestyle.”

The follow-up Pentagon memo claimed service members or recruits who have a history of, or show signs of, gender dysphoria, the distress some feel when their bodies don’t align with their gender, are “incompatible with the high mental and physical standards necessary for military service.”

“Military service is a life of service. It’s a sacrifice,” Morgan said. “A lot of time, a lot of energy, a lot of performance put into my ability to make lieutenant commander.”

As the courts and the administration respond, Morgan thinks about how all of that could be ending.

The legal back-and-forth

The January night that Trump signed the executive order, Morgan waited to read it until after she and Christina got the kids to bed. She didn’t want to absorb its contents and meaning alone.

When they finally nestled down, Christina read it three times before Morgan got through it once. Then they spent hours talking through how the order would affect their future.

A ban wouldn’t just stop Morgan’s career in its tracks. It would severely disrupt her life and that of her family. It would sever the pathway to her pension and retirement, benefits she and her wife were depending on. The couple built their financial planning around a lifelong career in the military, Christina said.

“It just feels ruinous,” Christina said. “We have no idea how financially secure we’ll be this time next year.”

A federal judge in Washington, D.C., blocked the Trump administration’s effort Tuesday to ban trans troops from serving in the military. Photo by Tim McPhillips/PBS News

At a March 12 hearing in Washington, D.C., District Judge Ana Reyes had pressing questions.

She asked Justice Department attorneys if they had read some of the studies that formed the basis for the Pentagon’s justification for the ban. They indicated they hadn’t.

Reyes upbraided the attorneys for being unprepared and ordered a 30-minute break for them to read the material.

When court resumed, the judge walked through each study’s findings. She was skeptical of how the data led to the conclusions behind the ban, including the idea that openly serving trans service members affected military readiness or unit cohesion. Some of the studies the memo cited, she added, actually supported keeping trans people in the military.

The attorney defending the policy was in some cases unable to answer the judge’s questions directly.

Judge Reyes’ ruling contained several transcripts of exchanges with government attorneys about the administration’s stance on the trans military ban.

The following week, Reyes blocked enforcement of the ban. In her written opinion, the judge acknowledged that she had a lengthy text — a 79-page opinion — “but its premise is simple.”

“In the self-evident truth that ‘all people are created equal,’ all means all. Nothing more. And certainly nothing less,” she wrote.

The judge also drew attention to the ban’s language, calling it “unabashedly demeaning” and that the resulting policy “stigmatizes transgender persons as inherently unfit, and its conclusions bear no relation to fact.” Reyes also wrote that there’s no evidence that Trump or Hegseth consulted with military leaders before issuing the order or its policy.

DOJ attorneys have argued in court filings and hearings that the commander-in-chief is “constitutionally charged” with setting U.S. military policy and officials in the armed forces should have the ability to make decisions about service members without court interference.

Reyes agreed that the president has the power, even obligation, to ensure military readiness. But the judge pointed to times in history when, “Leaders have used concern for military readiness to deny marginalized persons.”

“First minorities, then women in combat, then gays,” she wrote.

A Justice Department spokesperson said in an email to PBS News that Reyes’ injunction “is the latest example of an activist judge attempting to seize power at the expense of the American people who overwhelmingly voted to elect President Trump. The Department of Justice has vigorously defended President Trump’s executive actions, including the Defending Women Executive Order, and will continue to do so.”

A Pentagon spokesperson said the Defense Department doesn’t respond to questions about ongoing litigation.

Demonstrators handcuffed themselves to the fence outside the White House in November 2010 to protest the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. Then-President Barack Obama signed a law repealing the policy the following month. Photo Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

Sasha Buchert, a senior attorney for Lambda Legal, one of the groups representing Morgan and other trans troops in their legal challenge against the ban, said the arguments the administration has raised about readiness and unit cohesion are repeating the “same hypotheticals and fearmongering,” she said. The Defense Department, she added, is still cleaning up the dishonorable discharges that some LGBTQ+ service members received under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

“This is just something we’ve repeated over and over and over again,” Buchert said. “It’s just an echo of a shameful past.”

Levi, who described rollout of the ban as “chaotic and unpredictable,” said that implementing a policy in this manner “is contrary to military operations and destabilizing to the force.”

“It’s confusing to command. It’s confusing to troops. And of course it’s confusing to the transgender service members,” the attorney said. “These are folks who are used to following orders, who are committed to following orders, and whose lives have really been dedicated to understanding rules and carrying out a mission.”

Serving through the policy shifts

After witnessing the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 2011, Kris Moore spent the next few years gradually coming out as trans to family and friends. Eventually, the sailor told his commanding officer, too, soon after starting hormone treatments in 2015 for his medical transition.

The crew was preparing to deploy to the Middle East. And Moore wanted to get ahead of any rumors because “the sailors are going to see a change in me very quickly, like whether it’s the voice change or stubble coming in,” he said. “On a ship, you’ve got to trust everyone around you. The person next to you has to know that you’ve got their back.”

A rumor, he said, would complicate the deployment, and at a time he could face a discharge for being trans – President Barack Obama wouldn’t officially end the ban on trans service members until the following year.

With the support of his captain, Moore stood before a much bigger audience — his fellow officers and chiefs on the ship.

He told everyone that he was raised as a girl. He said he was taking testosterone to transition to living as a man. He was willing to explain to anyone what being transgender meant.

“At the end of the day, we have a job to do,” he remembered telling the crew, “and I just want to put this out there and just be open and honest with all of you guys.”

He asked if anyone had questions and the room grew quiet.

“Are you happy?” one chief engineer blurted out.

That caught Moore off-guard. He wasn’t sure if it was a legitimate question. The engineer repeated it: She wanted to know if Moore, and his partner at the time, were happy.

Moore said yes.

“Then who gives a s*** what anyone else thinks?” she said.

It was the aggressive show of support that Moore needed. When the wardroom was dismissed, every single person came over and shook Moore’s hand or hugged him.

“I was just, like, waterworks,” he said.

Moore later followed the processes to change his name and gender marker on government documents.

The support he’s received from commanding officers and peers hasn’t wavered.

Commander Emily Shilling, a decorated Navy pilot with over 60 combat missions and high-risk work as a test pilot, spoke with PBS News’ Lisa Desjardins about her legal challenge to Trump’s executive order. Watch the segment in the player above.

When Trump tweeted in 2017 that trans people would not be allowed to serve “in any capacity,” Moore’s ship had just returned to port. Internet access on the ship is weak when out at sea, “so I was completely oblivious to what was going on in the world,” Moore said.

At lunchtime, a voice piped in over the ship’s announcement system. Moore was being summoned to the commanding officer’s cabin. Something was wrong – meals are “sacred time” for service members to unwind, he said.

The command master chief, who was also in the commanding officer’s cabin, had a worried look as she told Moore to come in and have a seat. She didn’t say much more.

Moore asked what happened. His captain unmuted the TV and pointed to the ticker scrolling at the bottom.

Moore couldn’t fully process the news, but he remembered how the captain responded: This doesn’t matter. This is not policy. This is a tweet. This is not how the military chain of command runs.

The White House released a policy a month later, prompting multiple legal challenges and reaching the Supreme Court. When President Joe Biden took office in 2021, he reversed the policy. Yet the pendulum is swinging back again, with Trump trying the ban in his second term.

The shifts in policy have put trans service members in a precarious position. Doors opened after being shut for so long and then suddenly closed again.

“I’m scared,” said Moore, who is not a plaintiff in either lawsuit against the ban. He’s been in the Navy since he was 18. He’s now 38, a few years from reaching retirement.

“I had all these dreams that are, one by one, starting to get crushed because I won’t be able to finish my 20 [active-duty] years or continue to serve,” he said.

As the Trump administration seeks to lift the court’s ruling, Morgan is trying to figure out where her next assignment will be.

She had orders to report to a duty station in Maryland but they were canceled on March 11, about two weeks after the Pentagon policy was released, her attorney confirmed to PBS News.

There’s been so much waiting. Waiting on the executive order. Waiting on the Defense Department policy. Waiting on the Navy’s policy. Waiting on the official separation date. Waiting on a court ruling and the next one after that.

“We are just focused on putting our uniforms on, going to work every day, doing our jobs the best that we can do until we can’t do them anymore,” she said.

Right now, her uniform waits in her closet at home.

PBS News’ Tim McPhillips contributed to this story.