Omer Jean Dixon Winborn still remembers the tomatoes and greens from her father’s garden.

“When I was growing up, I could go in the garden, wash a tomato off and just sink my teeth down in it, and it would be so sweet and good,” she said.

The tomatoes she finds at the grocery store today — hard, no taste — pale in comparison to those that grew in her father’s garden.

“Fresh stuff, oh — so, so much better,” she said.

READ MORE: How gardens enable refugees and immigrants to put down roots in new communities

Winborn’s childhood memories around the garden are among the stories a local library in Ypsilanti, Michigan, is collecting for an ongoing oral history initiative. Researchers for the Ypsi Farmers & Gardeners Oral History Project ask farmers and gardeners in the city to share stories on how they got started growing food for their families and communities, and what lessons could be gleaned from their experiences.

Winborn is a retired teacher, genealogist, and a trustee of Ypsilanti District Library, as well as the first person interviewed for the project.

Winborn’s parents had been sharecroppers in Brownsville, Tennessee, and they came to Michigan in 1944, as part of the Great Migration.

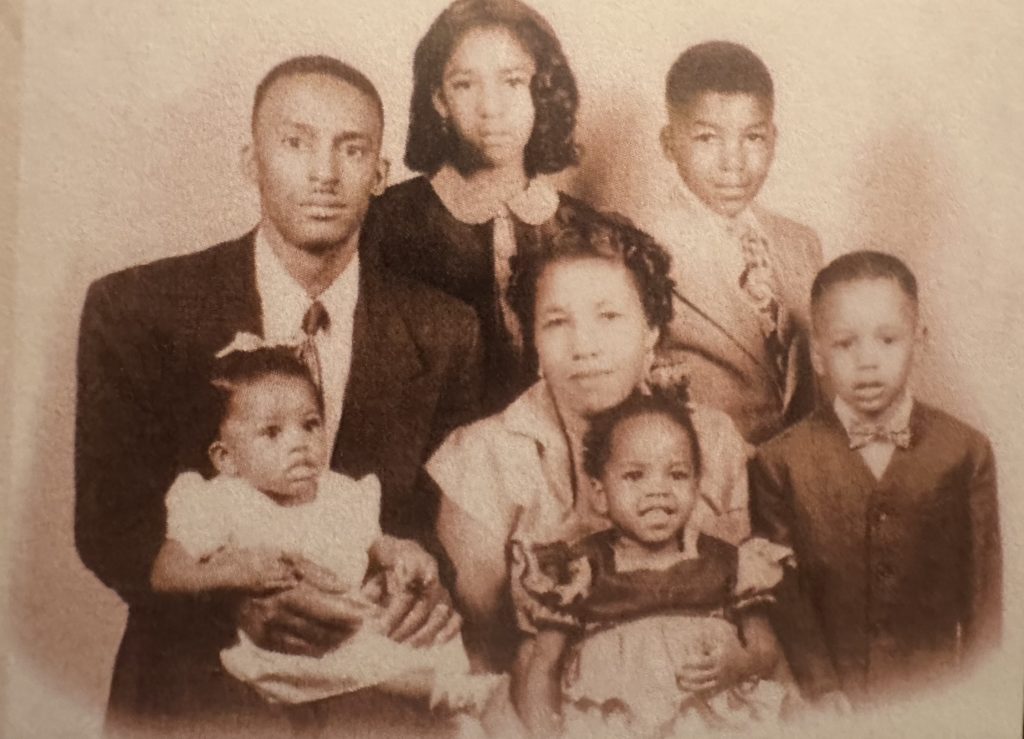

William and Minnie Allen Dixon and their children in 1955. Omer Jean Dixon Winborn is sitting on her mother’s lap. Photograph courtesy of Omer Jean Dixon Winborn

Her father, William Dixon, picked cotton for two years to save enough money to move north to join her mother and sister who had gone ahead to Ann Arbor.

After buying the family a house on North Fourth Avenue, which is in Ann Arbor’s historically Black neighborhood, he planted a huge garden on the vacant lot across the street and shared the vegetables and flowers with everyone in the community. They raised chickens in their backyard. Her mother, Minnie, would feed any of Winborn’s friends who happened to be at the house when dinner time arrived. There was always room for one more person at their table.

“Didn’t matter who it was. If they came over and it was dinnertime, they came in and ate with us,” Winborn said.

READ MORE: After leaving prison, returning citizens find new ground on this Michigan farm

Winborn is the main adviser for the oral history project, and she is also conducting interviews. The library is creating a digital archive to collect and share these stories of Ypsilanti’s food growers who are working class, Black, Indigenous, and other people of color.

“No one can tell your story except you,” Winborn said. “Everybody has their own story and it has to be told from their perspective, and doing oral history is the best way to get that person’s interpretation of their lives.”

Master gardener Patricia Wells’ oral history is featured in the Ypsi Farmers & Gardeners Oral History Project. She has trained with Keep Growing Detroit and Urban Roots. Photo by Nick Azarro, courtesy of Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project

The project launched in 2023 after Finn Bell, an assistant professor of human services at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, wanted to give back to the community that helped him with his dissertation research and share their stories. This year the project is expanding by adding a community advisory board and plans to conduct 20 more interviews. In this next phase, Bell especially wants to include more Indigenous farmers and gardeners who might want to share their stories.

This is a “particularly scary” moment because we’re living at a time “in which a lot of people growing food is more and more important,” Bell said. At the same time, there’s also been pushback toward an accurate telling of history and who gets to tell their stories, he added.

“One of the goals that the community set for the project is knowing what the history has been, how things used to be, so that we can build the future that we want,” he said.

Linda Bashert’s oral history is featured in Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project. She thinks of Ypsilanti as her eco-village and is a co-steward at Recreation Park Community Garden. Photo by Nick Azarro courtesy of Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project

Bell said he was “having an existential crisis about climate change” while working on his PhD dissertation. He began talking with people who helped the community become more resilient to climate change, including farmers and non-farmers who grow food. Earlier research he found about farmers in Ypsilanti focused only on white farmers and gardeners. Once he started talking to people in the community, he discovered that rather than any kind of “prepper” mindset to keep oneself and family safe in the face of climate change, people were asking a particular kind of question: What are we doing as a community to take care of all of us? People were also engaged “in ancestral lineages of growing food, in the ways that that is a part of these larger stories around the founding of the U.S. and enslavement and settler colonialism,” Bell said.

Growing food as a ‘kind of resistance’

Many of the things happening in the stories told in this oral history project are also happening in other places, Bell said.

“Ypsi is a microcosm of everywhere else in the U.S.,” Bell said. Growing food is a kind of resistance, a way for a community to “literally regain sovereignty, to regain some control and freedom over themselves, their bodies, their families, their communities.”

Omer Jean Dixon Winborn, Melvin Parson, Finn Bell, and research assistants Sasha Kindred and Briana Hurt are pictured at We the People Opportunity Farm in Ypsilanti Township, Michigan. Winborn and Parson’s oral histories are included in the Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project. Photo by Briana Hurt, courtesy of Ypsi Farmers & Gardeners Oral History Project.

One challenge in growing food is having access to land, which was historically stolen from Indigenous people and from formerly enslaved people after Reconstruction, Bell said. With that loss of land, people also lost ancestral wisdom and agricultural food growing legacies.

Bell also learned that small-scale food growers are increasingly important for building climate resilience, so that if one part of the food system fails, the entire system does not collapse. Huge monoculture commercial farming, or Big Ag, is fragile because when anything goes wrong, it is prone to large-scale failure, Bell said. In contrast, a network of lots of different small-scale farmers and gardeners who are growing different things on different lands, — “sort of like a quilt” — would not lead to the same sort of catastrophic failure, Bell said. When a lot of people grow food in concert with each other, that increases resilience for those individuals but also for the wider community.

READ MORE: Through gardens, these Native communities are cultivating a solution to climate change

Ypsilanti is also facing “really intense gentrification” right now, Bell said, something he attributes to policies and decisions of officials in Ypsilanti and neighboring Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan.

“There’s a long, long history of people growing food in backyard lots and side lots and abandoned land,” Bell said. “And as the value for those places rises, it’s becoming much, much, much harder for people to actually access land.”

The Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project research team with elders from the Generational Earn and Learn program at West Willow Community Garden, led by Linda Mealing, whose oral history is featured at the Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project. Photo courtesy of Finn Bell

The elders interviewed for the oral project have found the process healing because they are not just telling history for its own sake, he said: There is an intergenerational focus on using that history to build a better future for the community, by the community.

“It’s not enough to tell these stories in a vacuum, like we’re just recording the history but we’re not trying to change what’s happening in this moment. We need to obviously be doing both so that we can create the future that we want to live in,” Bell said.

Stories show what is possible

Abra Lee found a letter from the 1940s that her maternal grandmother in Ohio had written home to her mother, Lee’s great-grandmother, in rural Georgia. There was a simple line that read, “I got the potatoes you sent me.”

Lee’s great-grandmother had mailed some sweet potatoes from Barnesville, Georgia.

“A Georgia sweet potato from your family farm ain’t going to taste like an Ohio sweet potato, just because it’s from home,” Lee said. “That’s better than money, it’s like you sent me home. It was in your soil and you grew it and now it’s going to go to my body and feed me and bring me joy.”

READ MORE: Activists tap a sweet Indigenous tradition to connect youth of color in Detroit with the outdoors

Lee began studying the history of Black gardens when she was 26 years old and the landscape manager for Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, the world’s busiest airport. She felt a little imposter syndrome, she said, because she was so young. Her mother asked her who she thought took care of the grounds for the Tuskegee Airmen. “Even though I didn’t have a face or a name, of course, a Black person was in charge of aviation at Tuskegee for the Tuskegee Airmen,” Lee said. “Somebody has to keep the airfield cut, somebody has to manage the property.”

Her mother then told her about Charles William Costello, a wildly successful entymological artist from Ypsilanti.

Lee said that Costello learned how to paint and draw by copying the artists decorating the department store windows. Then one day, at a picnic, an insect fell into his cup. He became fascinated with the colors and the shapes of insects and began to draw and paint them. An Ohio State University professor happened to see his insect art at a small show, and then hired him to draw tens of thousands of illustrations for students to study at the school. He also worked for Wilberforce University, a historically black college.

Learning about Costello “just opened up this whole door. [My momma] wanted me to see that I wasn’t some newbie to ornamental horticulture,” Lee said. “I was from a long lineage of people, of my ancestors that had come before me. That was their gift. Their contribution to America was beautification and beauty as it applied to horticulture.”

Melvin Parson, who is featured in the Ypsi Farmers and Gardeners Oral History Project, is also the executive director of We the People Opportunity Farm, seen here in July 2023 in Ypsilanti Township, Michigan. Photo by Frances Kai-Hwa Wang/PBS News

Lee is working on a book that collects stories of Black farmers and growers across the country. “These stories are important, because people need to know what is possible,” Lee said.

Just as people need to have access to food, Lee believes that people also need to have access to beauty, regardless of economic status, and especially for Black communities.

“Beauty is a quality of life issue, and it is no less important to someone’s mental, physical, spiritual health than fresh food or water is. Beauty matters.”

READ MORE: Farmworkers are dying in extreme heat. Few standards exist to protect them

In her research, she discovered many “invincible garden ladies” in her family and in history, including Black women entrepreneurs in the 1920s and 1940s working with flowers and gardens and writing about beauty.

“Beauty is something that feeds muscle that’s going to carry me on the darkest days. I love that these women didn’t let people diminish what the power of beauty was and why people, regardless of your financial status, should have access to it,” Lee said.

She grew up with handmade quilts and heirloom roses on the front porch of her grandparents’ home in Barnesville, Georgia.

“I understand luxury and beauty because it was put in my lap from birth by these these these women, these invincible garden ladies,” she said.

Knowing about all these other people, she said, “just keeps me so grounded. It’s so safe. It’s like a quilt around me because it’s a guide. It’s like having these wonderful angels around you that are like, ‘We got you.’”

READ MORE: Through gardens, these Native communities are cultivating a solution to climate change

Winborn’s childhood home was full of flowers that her father grew in his garden.

Omer Jean Dixon Winborn holds flowers from her father’s garden for her bridal portrait. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1971. Courtesy of Omer Jean Dixon Winborn

“I could close my eyes right now, I can smell those roses,” she said.

Before she got married, a photographer came to her parents’ house to take her bridal photo. He asked if she had a bouquet, and she said no.

“My mom said, ‘Just a minute.’ And she went out and she picked flowers from out of the yard. And you can see them in the picture,” she said.

There were so many stories plucked from that garden, she added.