Florida leads the nation in executions this year and is on track to set new modern-day records.

The state is scheduled to execute another death row inmate this week — its ninth this year — surpassing its previous record of eight executions in 2014.

It matched that record earlier this month, when Michael Bernard Bell, a 54-year-old convicted for carrying out a double murder outside a Jacksonville bar in 1993, received a lethal injection on July 15.

Florida has three more executions on the calendar. The ninth execution, of Edward J. Zakrzewski, is scheduled on July 31. A 10th prisoner, Kayle Barrington Bates, has an execution date set for mid-August. An 11th prisoner, Curtis Windom, has one set for late August.

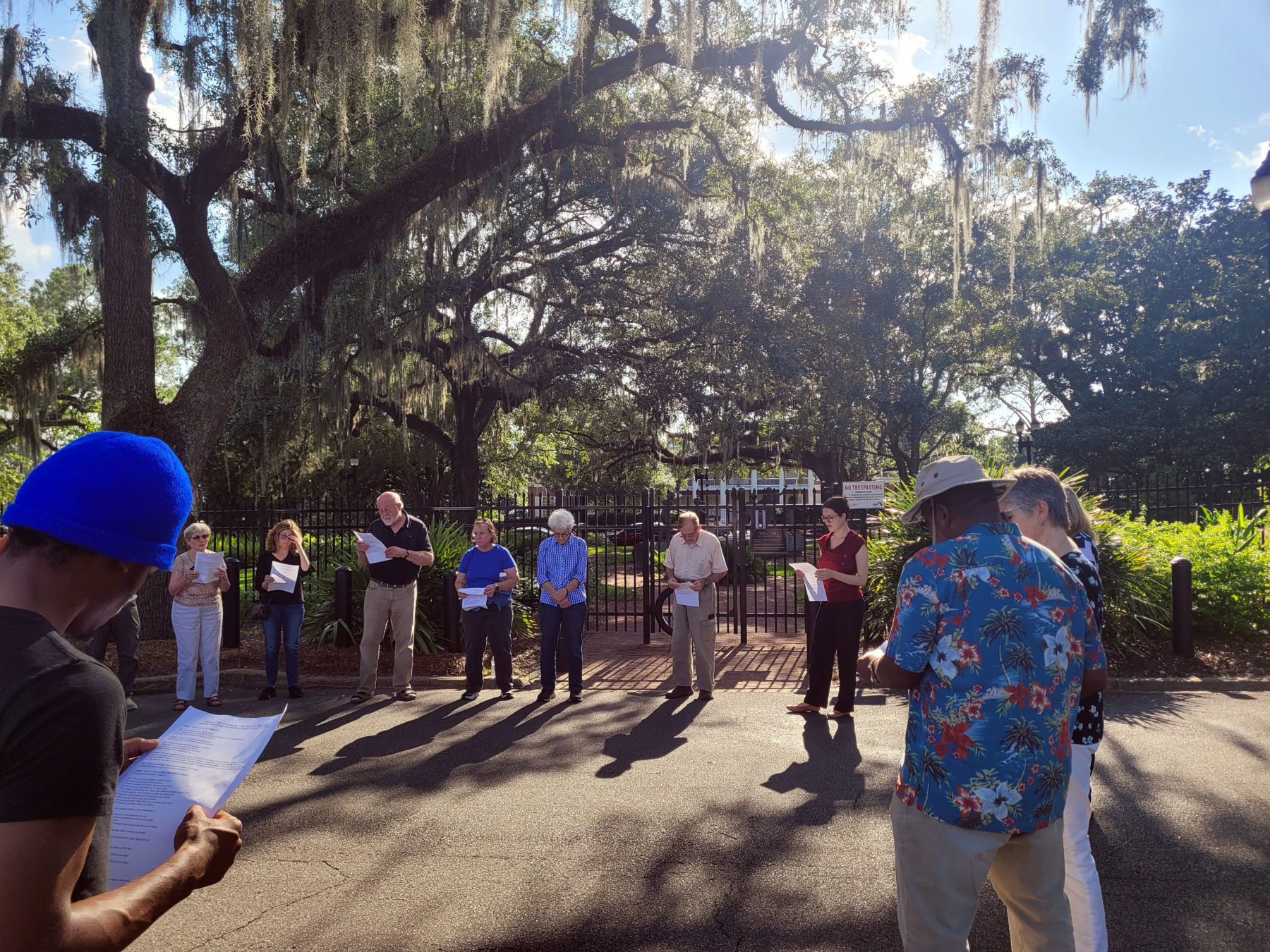

A vigil outside the governor’s mansion in Tallahassee, Florida, on the day of Michael Bell’s execution. Photo provided by Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Florida is leading the way at a time when U.S. executions are also higher than they were last year. Including Bell, 26 people have been put to death across the country about six months into 2025. Another 11 executions are scheduled for this year, according to the Death Penalty Information Center (DPI).

There were 25 executions in the nation for all of 2024, though experts told PBS News that the number of executions has largely remained low nationally.

While this year’s elevated number has made headlines, executions are a “lagging indicator” of where the public stands on the issue, said Robin Maher, DPI executive director. “They represent levels of support that are usually decades out of date.”

People on death row “were sentenced to death by juries usually many years, even decades, ago when public support for the death penalty was much higher and there were very different prosecution policies in place,” she added.

A much more meaningful examination of current public support for the death penalty would be how many new death sentences are being issued this year, Maher said.

Here are three things to know about the state of executions in the U.S.

As Trump promises to expand the death penalty, what are states doing?

In his flurry of Day 1 executive orders, President Donald Trump promised to restore the death penalty.

But each state decides whether and how it will use the death penalty, experts told PBS News.

“How a case proceeds is all controlled by state law and state constitution and federal constitution. There’s really no tie to executive order at the federal level to state capital systems,” said Amber Widgery, program principal for the National Conference of State Legislatures’ Criminal and Civil Justice Program, which has a database that tracks enacted capital punishment legislation.

Among the 23 states (and Washington, D.C.) that have already abolished the death penalty, Delaware is taking additional steps to revise its state constitution to prohibit the practice from being used as a form of punishment again. The mid-Atlantic state officially abolished capital punishment in September, eight years after its Supreme Court ruled its death penalty statute unconstitutional.

Currently, 27 states allow the death penalty, though governors in four — California, Pennsylvania, Oregon and Ohio — have placed a hold on executions.

There’s also been a number of states that have passed or are considering legislation that expands what would be considered to be capital offenses, Widgery said.

The Texas Legislature passed a bill, set to take effect on Sept. 1, that raised the penalties for the attempted capital murder of a peace officer. Pending legislation in other states, such as Ohio, Illinois and New York, would add capital offense charges in first-degree murder cases that involve victims who are peace officers, first responders, or members of law enforcement.

Other states have also enacted legislation that expands eligible capital offenses for cases involving child torture (Utah), human trafficking (Florida) or sex crimes, specifically where the victims are minor children (Arizona).

Two states have focused on the mental competency of individuals facing capital punishment, Widgery said.

Georgia passed a law in May that went into effect immediately that lowered its legal standard for proving intellectual disability in its death penalty cases. The measure, which received bipartisan support, puts Georgia in line with the other 26 states that permit the death penalty and have similar protections on the books for people with an intellectual disability, DPI said in its mid-year report. Also in May, Oklahoma clarified its process for determining mental competency for people facing execution.

The National Conference of State Legislatures’ database shows there’s been at least 20 enactments from all the state legislatures addressing capital punishment so far this year. In terms of volume, that’s somewhat higher than what was seen in previous years, Widgery said.

The level of legislative activity is less a metric about public favor for capital punishment and “maybe an indicator that this is an issue that is more of a topic for conversation this year than it has been in the last five years,” she said.

Despite the national uptick in executions this year, about 61% have been concentrated in three states, with Texas and South Carolina joining Florida, Maher said.

This is noteworthy, she said, because it shows “just how isolated in use the death penalty is.”

A better metric for tracking public support of the death penalty

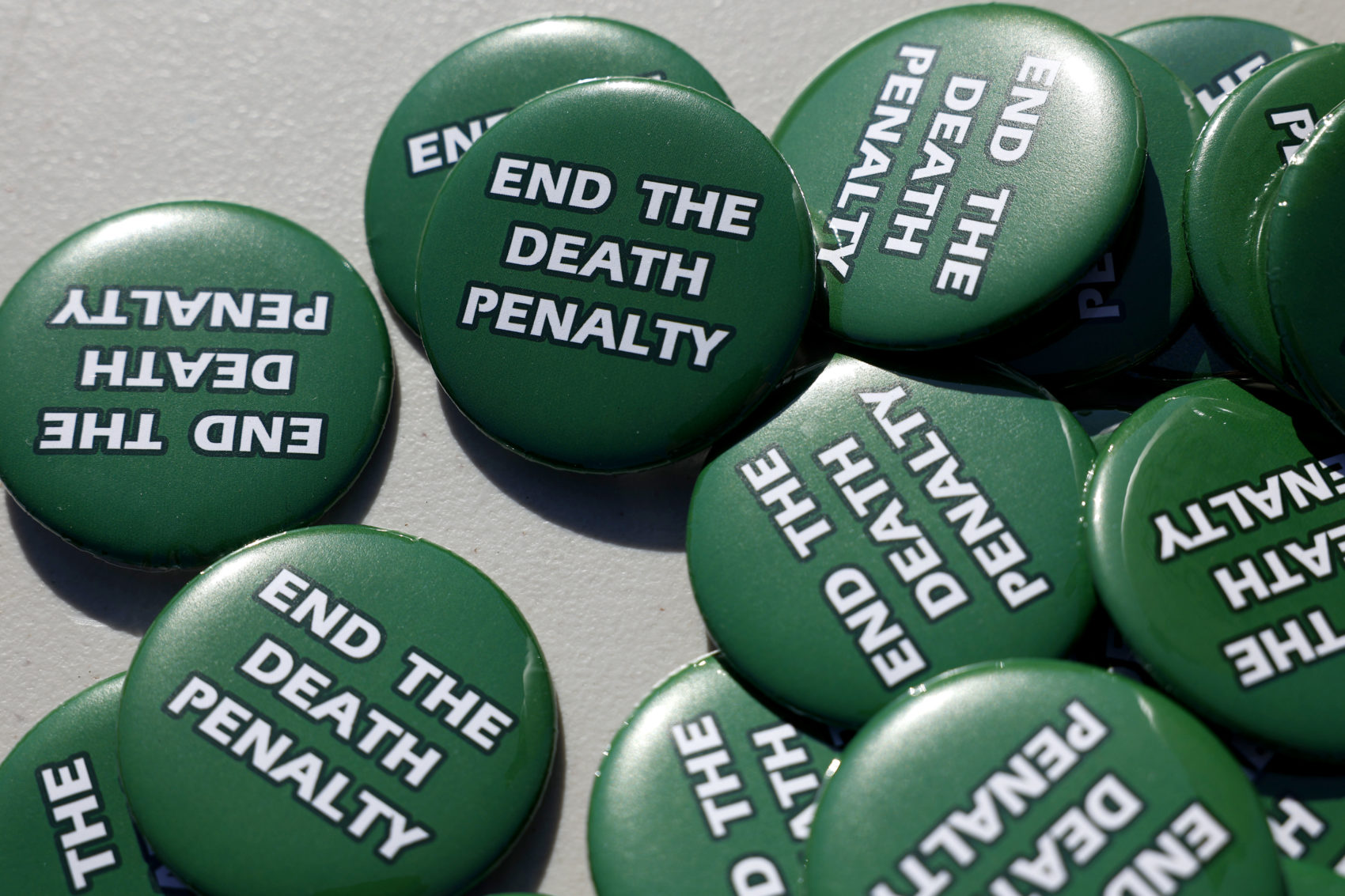

Pins opposing the death penalty sit on a table during a July 2024 demonstration outside the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Public support for the death penalty has largely trended downward since the mid-1990s. Gallup, which has tracked Americans’ sentiment toward capital punishment for years, released a poll in November that found that support for the practice remains at a five-decade low — 53% — in the United States. This drop in support is driven by younger generations of U.S. adults (millennials and Gen Z) who are less likely to favor the death penalty for convicted murderers, the pollster found.

The number of death sentences imposed each year has dropped significantly since 1996, which saw a record-setting peak of 316, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. In 2024, there were 26 new death sentences. The center, which usually documents new death sentences at the end of each year, said 10 people in six states have been sentenced to death around the six-month mark of 2025, a slower pace than during the same period in 2024.

That slowdown in new death sentences is “because juries understand so much more than they did 20 years ago,” Maher said. “They understand so much more about the effects of long-term trauma, the effects of intellectual disability and severe mental illness, brain damage, and they also have opinions about how effective the death penalty is and whether it is something that keeps communities safer.”

Brent Schneider, a 42-year-old U.S. Army veteran in Florida, attended his first vigil for an execution this year.

Shortly before Jeffrey Hutchinson was scheduled to be executed in May, Schneider changed into his old Army uniform. He joined dozens of death penalty opponents, other military veterans among them, outside the Florida State Prison in Raiford to oppose Hutchinson’s looming execution.

Schneider, now an assistant public defender, fought during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, about a dozen years after Hutchison fought during the Gulf War. Hutchinson, 62, was a paratrooper and U.S. Army Ranger. Hutchinson was convicted for the 1998 shooting deaths of his girlfriend Renee Flaherty and her three children.

Schneider felt that certain details of the case, such as Hutchison’s exposure to sarin nerve gas during the Gulf War, weren’t taken into account in court. He hoped his presence that day could help another veteran.

“If I put the uniform on, maybe that will be enough to register a demand signal with the right person,” he said.

Nearby Schneider outside the prison were two veterans who held up a sign that read in all caps: “All gave some, some gave all.”

During a vigil for Jeffrey Hutchinson, who was put to death in May, two veterans held up a flag outside the Florida State Prison. Photo provided by Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

Hutchinson’s attorneys argued in court that his military service resulted in permanent brain damage. Schneider joined a letter from 130 veterans that urged state Gov. Ron DeSantis to halt the execution, writing that Hutchinson “came home injured by war” and didn’t receive proper care.

“His mind was a casualty, just like any limb lost in combat,” the letter read.

These arguments were ultimately rejected. Hutchinson, who spent 24 years on death row, died May 1 by lethal injection.

Schneider used to believe in the death penalty. That changed, he said, once he started to explore his own views on capital punishment and human life, as well as learning more about the practice, such as the significantly higher costs associated with carrying out executions and the inequities of the criminal justice system.

“If the citizenry were better informed, I think views might change,” he said.

Whether it’d be significant enough to get rid of the practice is another question, he added.

Why is Florida executing more people this year?

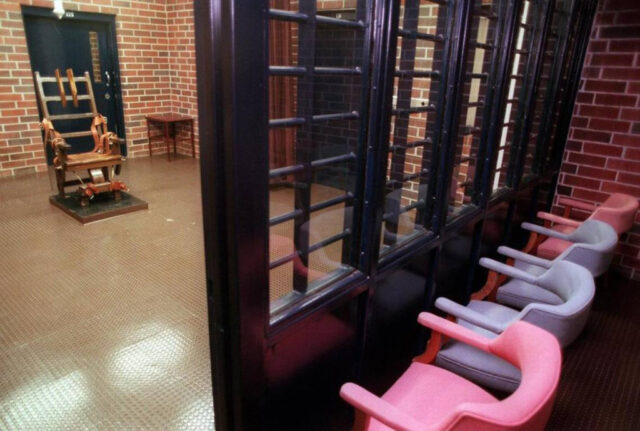

The Florida State Prison in Raiford where death row inmates are executed. Photo by Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Florida leads the nation in executions in a few notable ways, said Maria DeLiberato, executive director of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, a statewide organization that opposes executions.

Bell’s execution — Florida’s eighth this year — tied past records previously set by the state’s governors in 1984 and 2014. If the ninth execution goes ahead as scheduled on July 31, it will break the single-year record for any Florida governor. DeSantis’ pace, too, has been unprecedented, DeLiberato said.

“Florida, with its current leadership, has been one of those who’s trying to sort of appear tough on crime,” she said. The executive order Trump issued on the death penalty gives states cover to say they’re “just carrying out marching orders,” she added.

Last year, DeSantis signed only one death warrant, a document that formally sets the execution date when prisoners have exhausted all their appeals options. Loran Cole, convicted for the killing of an 18-year-old student in 1994, was executed by the state about 30 days after the governor signed the death warrant.

DeSantis has signed 11 death warrants so far this year. All these prisoners have been put to death within a similar 30-day timeframe.

DeLiberato, a capital defense lawyer, said the state’s elected leaders, including DeSantis, haven’t fully provided their reasoning for the increase in executions. As WUSF has reported, questions around the rationale for this ramp-up have grown, as have broader concerns over transparency on how the governor decides who lives or dies.

Florida also leads the nation in exonerations. Thirty people in Florida have been exonerated from death row since 1973, according to DPI.

“We get it wrong more than any other state,” DeLiberato said.

Ahead of Bell’s execution, some 100 faith leaders sent a letter to DeSantis, calling for a pause on the death penalty in the state.

DeSantis, who supports capital punishment, told a crowd in May that some crimes are “so horrific the only appropriate punishment is the death penalty.”

The governor did not respond to a request from PBS News for comment.

Florida joins Alabama as the only two states where unanimous juries are not required for death penalty sentences. Florida reduced that requirement in 2023, meaning juries can recommend someone for death row with an 8-4 vote.

While DeSantis and other state leaders have worked to expand the death penalty in the state, DeLiberato said that’s not necessarily reflective of everyday Floridians.

A jury rejected the death penalty in June for Ronny Walker, who was convicted of first-degree murder of a 14-year-old girl, and instead recommended a life sentence.

“We are still seeing juries voting for life, even under the non-unanimous system,” DeLiberato said.

Across from the Florida State Prison, where all the state’s executions take place, there’s a field with designated spots for people who support and oppose the death penalty.

On the days of a scheduled execution, a church in Daytona Beach that advocates for the end of capital punishment organizes bus trips to the prison to hold prayer vigils for the soon-to-be-executed and their victims. Dozens of death penalty opponents typically attend the vigils, DeLiberato said.

Sometimes, there are individuals who show up in support of the death penalty, though this is rarer, she said. It’s a far cry from the scene outside the prison when serial killer Ted Bundy was electrocuted more than 35 years ago. The moment drew hundreds who celebrated his execution.

Ted Bundy’s image on a television screen set up on the lawn outside the Florida State Prison on the day of his execution in 1989. Photo by Bettmann via Getty Images

Before Anthony Wainwright’s execution in June, some members of the victim’s family showed up, supporting the death penalty.

A couple other times, there has been a single supporter who holds up the same sign, DeLiberato said. He didn’t appear to be connected to any case.

Whoever the last person was that was executed, he crosses out their name and writes in the next prisoner’s name.

Other than those instances, DeLiberato said, the spot for death penalty supporters these days is almost always an empty field.

We’re not going anywhere.

Stand up for truly independent, trusted news that you can count on!