For years now, every year, unfailingly, when the new academic year begins across the country, newspapers report horrifying examples of ragging in our colleges and universities, specifically in residential medical, engineering and technical campuses.

Let me give some examples of this horror: stabbing someone with a divider in a nursing college hostel; tying youngsters to cots and hanging dumbbells from their genitals; being lashed with a belt by a senior; being hit on the head with a steel bottle; being forced to stand for hours; stripping young students and forcing them to perform sexual acts against a wall and other similar incidents. In recent years, ragging has further expanded into discrimination, harassment and bullying based on the caste, class, and sexual orientation of new students.

According to a report released in March 2024 by an anti-ragging NGO, Society against Violence in Education (SAVE), during the period 2022 to 2024, the National Anti-Ragging Helpline received 3156 complaints from 1946 colleges through phone calls and e-mails. The report clarifies that this number is not the total number of complaints regarding ragging because a large number of complaints were directly made to colleges and to the police. Further, only a small number of victims muster enough courage to actually complain. Thus, the actual number of ragging incidents in the country is much higher.

The report identifies medical colleges as the hotspots of ragging: they account for 38.6 per cent of total complaints, 35.4 per cent of serious complaints and 45 per cent of ragging-related deaths despite making up only 1.1 per cent of total students in the country.

A total of 51 deaths took place during this period, with 20 deaths in 2024 alone! During 2022-24, among medical colleges, maximum complaints were received from the MKCG Medical College and Hospital, Odisha, and Madhya Pradesh Medical Science University, Jabalpur.

Among other colleges and universities, Banaras Hindu University received the highest ragging complaints, while among other universities, Malians Abdul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal, tops the list.

Though the Supreme Court defined ragging as any act ‘which causes or is likely to cause annoyance, hardship or psychological harm or raises fear or apprehension thereof in a fresher or a junior’ way back in 2001, while hearing a petition regarding increasing ragging cases in colleges, it was only in 2009 that the then central government appointed a committee to suggest anti-ragging measures after large-scale protests following the death of a medical student in a college in Himachal Pradesh during ragging! Later that year, for the first time, the UGC issued regulations to curb ‘the menace of ragging in higher educational institutions’.

These regulations were last amended in 2016 to define ragging as ‘any act of physical or mental abuse (including bullying and exclusion) targeted at another student (fresher or otherwise) on the grounds of colour, race, religion, caste, ethnicity, gender (including transgender), sexual orientation, appearance, nationality, regional origins, linguistic identity, place of birth, place of residence or economic background’.

Though the above definition is wide-ranging and captures the entire range of possible bases for ragging, surprisingly, as yet, there is no uniform, central law to deal with ragging complaints in the country. In 2019, a bill against ragging was introduced in Parliament by a Congress leader, but it has not yet been passed! Some state governments have passed anti-ragging laws: Tripura passed such a law way back in 1990. Tamil Nadu was the first state to completely ban ragging in its educational institutions and criminalised it through an act in 1997. Between 1997 and 2000, some other states like Kerala, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal passed their own anti-ragging laws and provided for punishment for ragging ranging from fines to expulsion to even a jail term in extreme cases.

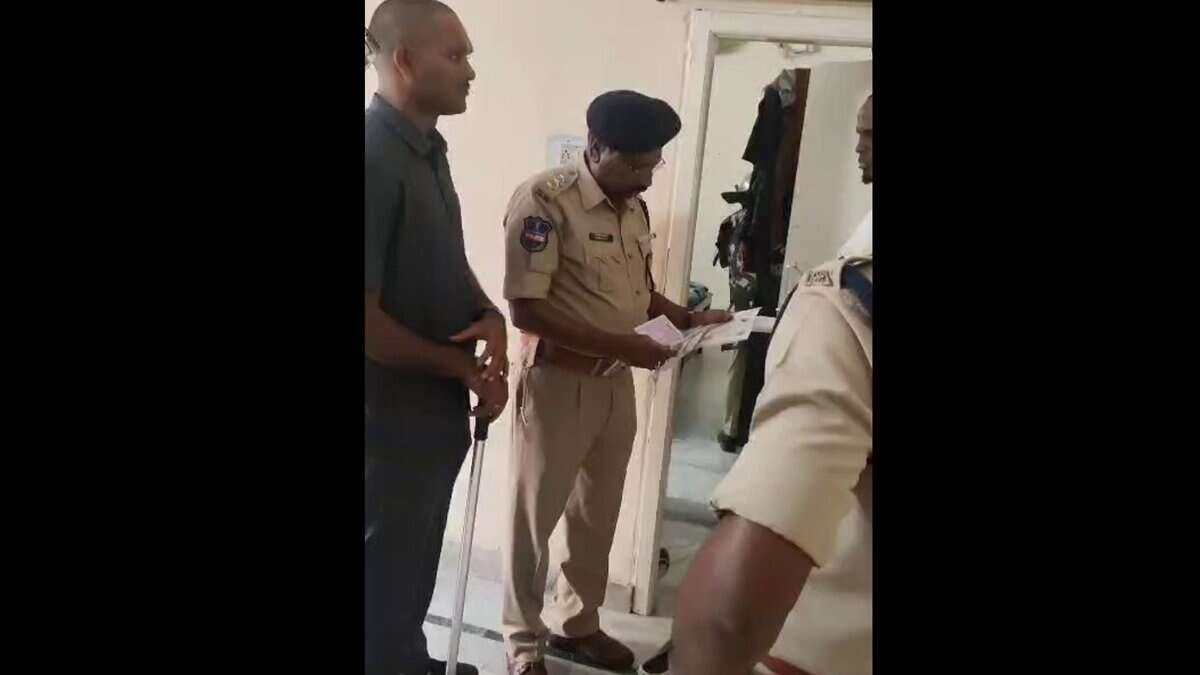

However, the menace continues, primarily because there is no administrative and political will to seriously confront the problem. All too often when such an incident is reported to college authorities, they seem more keen to protect the reputation of their institution than help the victimised student. When it is found, as happens in most cases, that culprits belong to powerful groups and political parties, institutional attempts are made to cover up the incident rather than punish the culprits. In fact, in some cases, college management forced the victims to give written declarations that they were never ragged! Further, many college managements dismiss ragging as a benign rite-of-passage ritual and often treat these complaints as frivolous. Not surprisingly, a few young students feel so deeply humiliated that they commit suicide; some get into depression; some simply leave.

An office-bearer of SAVE said that through an RTI application, they found that hardly 5 per cent of institutions follow the UGC guidelines regarding anti-ragging measures. Despite its regulations, in a reply to an RTI query, the UGC itself admitted that it has not taken strict action against any institution for failing to curb the menace of ragging on its premises.

Experts suggest that no anti-ragging measure is likely to work in any institution properly unless effective mechanisms for reporting cases, protecting the victim and swiftly punishing the culprits are in place. But for all this to happen, first the UGC and college managements need to treat ragging as a serious offence. Unless this crucial first step is taken, the menace will continue to haunt our institutions of higher education.

Vrijendra taught in a Mumbai college for more than 30 years and has been associated with democratic rights groups in the city.