Read about India’s evolving role within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s leadership. India has transitioned from an observer to an active member of SCO, promoting a multi-faceted agenda beyond traditional security concerns, which is aligned with Modi’s “SECURE” framework. There are opportunities as well as challenges India faces in the SCO.

Redefining relations with Central Asia: India’s transformative role in the SCO under PM Modi – a comprehensive article that covers all these aspects.

INTRODUCTION

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is now a critical pillar of Eurasian diplomacy, with an agenda and reach that extend far beyond its roots as a regional security union. The SCO, founded in 2001 and currently including eight member states including heavyweights such as China, Russia, and India is positioned at the intersection of Asia’s most pressing economic, political, and strategic concerns.

As the organization’s annual summit takes place in Tianjin, China, from August 31 to September 1, 2025, global attention focuses not only on the deliberations, but also on the high-stakes context that shapes them: a world economy rattled by renewed US tariff escalations under President Trump, intensifying regional rivalries, and a charged broader debate on the future of multilateralism.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s involvement takes on significant importance in this context. Modi’s visit, which will be his first to China in seven years, demonstrates India’s renewed dedication to Eurasian cooperation at a time when trade disputes and disruptions to global supply networks threaten the foundation of international alliances.

Expanding the scope of the SCO has been made possible in large part by Modi’s leadership, which is marked by diplomatic ingenuity and an ambitious agenda. India has transformed the organization into a platform for security and comprehensive, people-centered collaboration under his leadership by supporting programs in digital inclusiveness, entrepreneurship, traditional medicine, youth and cultural exchanges, and the preservation of Buddhist legacy.

Despite these aspects, some analysts have gone so far as to say that India need to think about leaving the SCO since it is a Chinese-dominated organization and its membership serves no strategic, political, or economic goals. This is a terribly ill-advised and shortsighted way to think.

This paper examines how PM Modi has helped the SCO move toward multifaceted involvement while also changing India’s place within the group. The SECURE framework, which he has promoted at past summits, is at the heart of this story. It is a holistic vision that combines security, economic growth, connectivity, cultural rapport, environmental sustainability, and educational exchange as the cornerstones of regional peace and prosperity.

This paper will analyze PM Modi’s tactics, the relevance of his ambitions in a changing global order, and the opportunities they present for India’s future as a defining power in Eurasian affairs by placing India as a major architect of the SCO’s expanded mandate.

OVERVIEW OF SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION

The SCO is a regional multilateral organization that prioritizes economic growth and security. It was founded in 2001 by Russia and China. China’s top concern following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 was the safety and stability of its western border, which had always been at risk. China was eager to resume the delayed negotiations to settle the long-standing border dispute that former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had started in 1986. The lengthy border talks between China and the four Soviet Union successor states Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan that shared boundaries came to an end in 1996.

In order to maintain the momentum of friendship in the post-settlement era, China took the initiative and joined forces with Russia to form the “Shanghai Five” in 1996. Therefore, the idea behind the Shanghai Five was to maintain peace and stability along the vast border between these five nations. In 2000, the Dushanbe summit decided to turn the Shanghai Five into a regional association. In 2001, it was succeeded by SCO.[1]

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization Charter was signed in 2002 at a meeting of the Council of Heads of State in St. Petersburg, and it went into effect on September 19, 2003. It is a statute that establishes the organization’s goals, ideals, structure, and primary areas of activity.[2]

The primary goals of the SCO are to foster mutual trust and good neighbourly relations among member states; to enable effective cooperation in a wide range of fields such as politics, economics, science, technology, and culture; to jointly safeguard regional peace, security, and stability; and to promote a democratic, fair, and rational international order.[3]

With well-structured layers of dialogue mechanisms ranging from annual summit meetings between heads of state and parliament to numerous ministerial-level meetings covering defense, foreign affairs, internal security, economic development, and finance, the organization has progressively institutionalized over the past 20 years. The SCO consists of two permanent bodies: the Secretariat, based in Beijing since 2004, and the Regional Anti-Terrorism Structure (RATS), formed in Tashkent in 2005. The SCO promotes economic and energy cooperation among its member states.

The Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) of the SCO was established in 2004 and operates out of Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Information sharing and operation coordination pertaining to terrorist training facilities and funding sources are part of RATS’s duties. RATS is currently attempting to bring all of the member nations’ anti-terrorist laws into uniformity. RATS submits its reports to the UN and other international bodies.[4]

INDIA AND SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANISATION

India was admitted to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as an observer at the 2005 Astana Summit. Since then, India actively participated in SCO operations as an observer, often represented by its foreign minister. India sees the SCO as a valuable venue to address its concerns in the Eurasian region, particularly regarding security and economics. India expressed a strong desire to become a full member and participate effectively since its inception.

Prior to Narendra Modi’s election in 2014, India had mostly served as an observer in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) since 2005. During this period, India’s involvement with the SCO was cautious and restricted.

In September 2014, during the SCO Heads of State Summit in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, India formally applied for full membership in the SCO.[5] India’s External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj stated, “We have given new energy and momentum to our ties with our immediate and extended neighbourhood.” Our administration is committed to increasing involvement with the SCO and making a more meaningful contribution to its activities. She stated, “We have submitted a formal application for full membership in the SCO to the current chair.” We aim to establish a new engagement with the SCO region, using our historical ties while preparing for the difficulties of the 21st century.[6]

Central Asian Republics supported India’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. India was considered as a soft balancer against big powers China and Russia, strengthening their multi-vector foreign strategies.[7]

INDIA’S STRATEGIC LEVERAGE IN SCO: THE ROLE OF CENTRAL ASIAN REPUBLICS

One of the primary goals of the SCO was to offer a framework for close cooperation with newly established Central Asian states to ensure peace and security in the dangerous region, including resolving boundary issues and countering transnational terrorist and separatist groups. As a result, Article 1 of the SCO Charter, which outlines the organization’s primary “goals and tasks,” exhorts member nations to “jointly counteract” the three evils of “extremism, terrorism, and separatism in all their manifestations.”

India’s reputation as a stable democracy and its proficiency in counterterrorism are major contributors to its strategic influence in Central Asia. This view is further supported by the SCO’s development as a security mechanism. The group “has expanded its agenda from border security to encompass terrorism, extremism, separatism, and drug trafficking,” as Aris (2009) describes.

In order to strengthen India’s reputation as a frontline state against terrorism, New Delhi can coordinate intelligence, training, and operational procedures with CARs through the SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS).[8]

In addition to acknowledging its growing geopolitical influence, India’s full membership in June 2016 provided a direct path to further relations with the Central Asian Republics (CARs) Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.[9]

Central Asia’s geopolitical location as Eurasia’s heartland, its resource-rich character, and the tense security situation in Afghanistan following the return of the Taliban have all put the region at the forefront of the SCO’s attention. Russia’s conflict with Ukraine has also created a vacuum, resulting in fierce competition among major external parties, including China and other states. Central Asian republics, in turn, have attempted to deter external power play by utilizing their ‘Multi-Vector’ foreign strategies. This has created opportunities and difficulties for India.

Russia and China have generally led the SCO, using it to consolidate their power in Central Asia. However, India’s membership provides a third pillar, reducing the organization’s bipolarity and increasing its multipolarity. Renowned research analyst Poonam Mann writing in Air Power Journal states that, “India can be welcomed as the third pillar of the SCO” because its membership offers the Central Asian republics with “a soft balancer against the two leading powers”.[10] As a result, India’s strategic influence comes from both its independent weight and its contribution to the CARs’ increased autonomy in forming their multifaceted foreign policy.

CENTRAL ASIA AS INDIA’S EXTENDED NEIGHBORHOOD

India has always made it clear that the CARs are part of its “extended neighbourhood”.[11] Geographical obstacles and Pakistan’s blocking of transit routes have kept India’s influence in the area small despite strong civilizational and cultural ties that date back to ancient trade routes, Buddhism, and Persian cultural interactions.

“India’s transit to the region lies through Pakistan and Afghanistan, thus limiting India’s reach in a pure physical sense,” Mann notes as a significant limitation.[12] Therefore, both innovative connection initiatives and more robust global participation are needed to overcome this obstacle.

Due to insufficient and sporadic communication between India’s senior leadership and Central Asia, India has not been able to deepen its connection with these nations. The ability for India’s prime minister, ministers, and senior officials to interact with the presidents and counterpart ministers and officials of the four Central Asian nations (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) is perhaps the biggest benefit of the SCO for India.

Central Asia’s strategic importance is derived from its massive energy reserves and mineral wealth. Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan collectively own some of the world’s largest oil and natural gas deposits, while Kazakhstan controls roughly a quarter of worldwide uranium reserves.[13] These resources are critical for India’s energy-intensive economy.

The CARs also serve as a strategic link between South Asia, Eurasia, and Europe, making them critical to India’s connectivity efforts. If a feasible method of transporting these minerals from the region to India can be established, these nations can successfully help meet India’s energy security needs. Due to the unfavorable security conditions in both Afghanistan and Pakistan, the TAPI (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India) gas pipeline project has been ongoing for many years but has not advanced much. India has been trying for years to develop connection through the International North-South Transport Corridor and the Chabahar seaport in Iran to address the lack of border continuity. While development on both projects has been gradual, recent years have seen greater activity and significant forward momentum.[14]

Relationships between India and the Central Asian Republics are not just strategic, they are also advantageous to both parties. The CARs desire diversification of alliances to safeguard their sovereignty, whereas India needs dependable allies in energy, security, and diplomacy. Both face the common challenges of violent extremism, transnational criminality, and geopolitical fragility under the shadow of greater powers. Through the SCO, India may formalize these alignments into a cooperative framework.

CONSTRAINTS ON INDIA’S INFLUENCE

Notwithstanding these advantages, India does not have total influence. “China and Russia retain the ability to block initiatives that do not serve their interests” in the SCO, which is still a consensus-driven institution. Therefore, institutional inertia and the veto power of larger countries may limit India’s actions. Furthermore, India’s aspirations are complicated by its lack of direct geographic access to Central Asia. Implementation is frequently slowed by regional instability, even if Iran’s Chabahar port and the INSTC provide partial solutions.

India’s aim is further complicated by Pakistan’s membership in the SCO. “India and Pakistan’s simultaneous entry into the SCO created an inherent contradiction,” as Mann observes.[15] This dynamic frequently hinders agreement on delicate matters, weakening the organization’s capacity for decisive action. India must therefore acknowledge the structural constraints of the SCO framework and strike a balance between assertiveness and pragmatism.

Thus, the future of India’s Eurasian strategy will be determined not just by bilateral initiatives with the CARs, but also by how successfully it navigates the SCO’s institutional dynamics. This balancing act contains both the potential and the hazard of India’s Central Asian commitment.

PM MODI’S STRATEGIC VISION FOR SCO

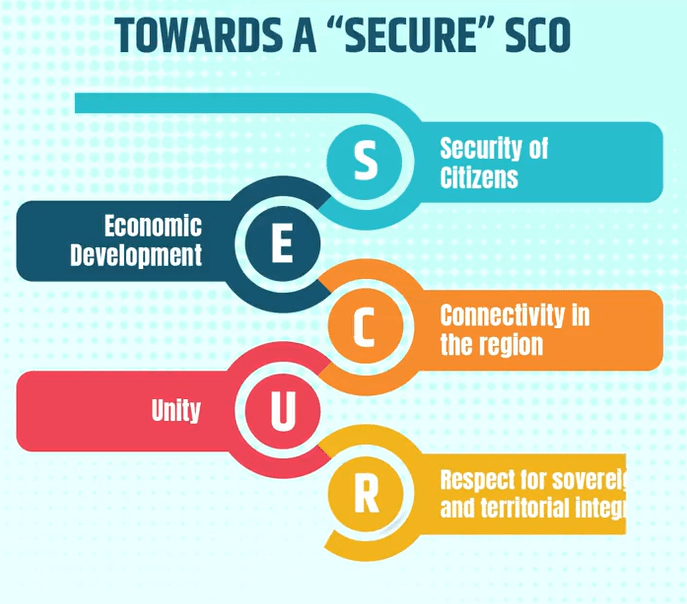

Since India’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has outlined a strategic vision that has steadily changed the organization’s agenda and expanded its scope to address modern regional and global concerns. PM Modi’s strategy is best characterized by the acronym “SECURE,” which was introduced at the 2018 SCO Summit in Qingdao, China. This vision is based on six pillars: Security, Economic development, Connectivity, Unity, Respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, and Environmental protection, all of which reflect India’s holistic priorities within the SCO framework.[16]

India actively took part in SCO events from 2017 to 2020, encouraging further technology cooperation and economic integration. India positioned itself as a leader in tech-driven multilateralism inside the SCO by advocating for enhanced transit regimes, deeper commercial ties, and increased collaboration on digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence.

India demonstrated its capacity to lead SCO activities in the face of the worldwide pandemic in 2020 by hosting the SCO Council of Heads of Government meeting virtually. In order to build stronger people-to-people ties, Modi’s government broadened the agenda during this time by promoting collaboration in new areas like startups, innovation, traditional medicine, youth empowerment, digital inclusion, and cultural exchanges.[17]

India assumed the SCO rotating leadership in 2023, hosting the Council of Heads of State summit virtually in July. Under its leadership, India established five new cooperation pillars that represent contemporary concerns and aspirations: innovation and entrepreneurship, youth empowerment, traditional medicinal systems, digital inclusiveness, and common Buddhist heritage.[18] These activities emphasized India’s desire for a more people-centered, modern SCO. Furthermore, the addition of new members such as Iran and Belarus during this time period indicated a significant increase in the organization’s geographical and strategic impact, indicating India’s involvement in extending the multilateral structure.

India continuously emphasized the value of upholding territorial integrity and sovereignty throughout this time, which is essential for fostering confidence among SCO members. By promoting SCO-wide commitments to climate action, sustainable development, the advancement of renewable energy, and the decarbonization of the transportation sector, Modi also raised awareness of environmental issues.[19]

THE SECURE FRAMEWORK AS A CENTRAL ORGANIZING IDEA

Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduced and championed the SECURE framework, which provides a strategic and comprehensive vision for the future of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). It aims to go beyond traditional security paradigms and construct a multidimensional cooperation model that incorporates economic development, connectivity, cultural diplomacy, environmental sustainability, and education alongside traditional security concerns.

WHAT IS SECURE FRAMEWORK?

Prime Minister Modi unveiled the acronym ‘SECURE’ at the 2018 SCO meeting in Qingdao, China, and explained the semantic importance of each letter in the phrase. The speaker emphasized the importance of the six elements: S for citizen security, E for economic growth, C for regional interconnectivity, U for unity, R for respect for sovereignty and integrity, and E for environmental preservation.

At a recent SCO meeting, Union Defence Minister Rajnath Singh emphasized the importance of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘SECURE’ project, which demonstrates India’s commitment to strengthening the region’s overall welfare and inclusion.[20] Minister Rajnath Singh went on to clarify that each alphabet in the word ‘SECURE’ represents India’s unshakable commitment to specific facets of regional development. To begin, the letter ‘S’ stands for Security of Citizens, emphasizing India’s commitment to the safety and well-being of people living in the SCO region. The letter ‘E’ denotes economic development for all, emphasizing India’s commitment to promoting inclusive growth and prosperity for all member states. ‘C’ stands for Connecting the Region, underlining the need of improving connectivity through many means such as infrastructure development and digital connectivity. The letter ‘U’ stands for Uniting the People, indicating India’s desire to foster people-to-people relations and cultural cooperation among SCO member countries. SECURE is a shorthand for the main ideas that underpin the SCO’s changing agenda under Modi’s direction.[21]

PM MODI’S ADVOCACY AND PROMOTION OF SECURE IN SCO FORUMS

Prime Minister Modi has continuously underlined the SECURE framework at numerous SCO conferences and talks. His talks emphasize that a single focus on security is insufficient to handle the region’s difficulties, and that comprehensive collaboration across economic, cultural, and environmental domains is required for long-term peace and prosperity.

For example, throughout the SCO summit cycles chaired by India and at global forums, Modi emphasized the importance of integrating innovation and startup ecosystems into the SCO agenda, as well as supporting the use of digital tools to improve regional connectivity and inclusivity. He has also highlighted traditional medicine collaboration, youth participation, cultural linkage, and a focus on Buddhist legacy as distinct soft power characteristics that correspond with SECURE’s cultural and educational goals.[22]

IMPACT OF SECURE ON SCO’s POLICIES AND PROJECTS

India’s efforts to establish the SCO Working Group on Traditional Medicine and a new Task Force on Startups and Innovation to exchange experiences with SCO member nations would contribute to the development of economic cooperation within the SCO region, which will benefit common people in real-world ways.[23]

The SCO’s actions have expanded beyond its initial remit of counterterrorism and regional security since its inception, led by the SECURE framework. The framework has provided coherence to numerous efforts:

SCO STARTUP FORUM

The SCO Startup Forum provides a forum for stakeholders in the startup ecosystems of all SCO Member States to engage and collaborate. The entrepreneurship initiatives seek to empower local startup communities in the SCO Member States. The SCO Startup Forum seeks to foster multilateral cooperation and engagement for startups among SCO Member States. This participation will strengthen the local startup ecosystems in the SCO Member States.

The engagement aims to achieve the following goals:

(i). Best practices are shared to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship and create knowledge-exchange networks.

(ii). Bringing in corporates and investors to collaborate closely with startups and give local business owners access to markets and much-needed support, expanding company scaling prospects by offering social innovation solutions and supplying governments with a wealth of creative alternatives.

(iii). Establishing transparent procurement channels to facilitate matching in order to get creative solutions from startups

(iv). Facilitating programs for cross-border incubation and acceleration that will allow businesses to investigate global markets and receive targeted mentoring.

At the 2022 SCO Heads of State Summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, member states agreed to establish a Special Working Group for Startups and Innovation (SWG). Given the importance of innovation and entrepreneurship in growing and diversifying an economy, India launched this initiative in 2020 to establish a new pillar of cooperation among SCO Member States. The SWG was established with the goal of encouraging collaboration among SCO Member States in order to benefit the startup environment while also accelerating regional economic development. After several rounds of meetings led by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), Government of India, the Member States resolved to ratify and adopt the SWG Regulations, which will be headed permanently by India in SCO.[24]

Since 2020, DPIIT has organized a number of programs for the SCO Member States’ startup ecosystems, such as three SCO Startup Forums. India seized the chance to broaden the innovative footprint by spearheading these engagements, tying the entire ecosystem together and encouraging other SCO Member States to launch like initiatives.

SCO AND COOPERATION ON TRADITIONAL MEDICINE

Under the auspices of the Ministry of Ayush and India’s SCO presidency, the B2B Conference and Expo and National Arogya Summit, which took place in Guwahati in 2023, successfully brought together 25 SCO nations to promote traditional medicine in order to help with economic development, environmental protection, and the attainment of the SCO nations’ goal of health security. During India’s SCO Presidency, the Ministry of Ayush organized a virtual conference of traditional medicine experts and practitioners, as well as the First Expert Working Group (EWG) on Traditional Medicine, which approved the EWG’s Draft Regulations on Traditional Medicine.[25]

SCO YOUNG SCIENTIST CONCLAVE

The plan to regularly organize youth events (forums, contests, etc.) was endorsed by the fifth session of the Heads of Ministries and Departments of Science and Technology of the SCO Member States, who acknowledged the immense talent among SCO youth and approved India’s request to host the SCO forum for young scientists and innovators on its territory. India hosted the second SCO Young Scientists Conclave from October 10-14, 2022, in a hybrid format with a preference for in-person attendance.[26]

SCO PEOPLE TO PEOPLE TIES

Engagement on a cultural and interpersonal level is one of the cornerstones of India’s connection with the area. Indian filmmakers, poets, and writers are well-known throughout the region. The cultural affinities, shared understandings, and preferences of people from India and Central Asia might strengthen their bonds. Aspects of Buddhism, Jainism, Sufism, and a rich literary legacy connect Central Asian nations and India together in shared cultural perspectives. Telemedicine, healthcare, and India’s technical cooperation program have all directly benefited and gained popularity among the region’s common people.

In the spirit of cultural-humanitarian cooperation, India hosted the first-ever SCO virtual 3D digital exhibition on shared Buddhist heritage in 2020. The National Museum of New Delhi, in active collaboration with SCO member countries, created a one-of-a-kind digital exhibition on shared Buddhist legacy that featured exquisite and rare treasures. The exhibition also revealed numerous Buddhist art traditions that cross national borders, rendering similar subjects that invite comparisons between regional aesthetics while identifying characteristics distinct to each area.[27]

IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE TRAJECTORY

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and regional cooperation in Eurasia will be profoundly and extensively impacted by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s agenda for the organization. In a conference that has traditionally been controlled by China and Russia, Modi has cleverly positioned India as an agenda-setter and an active member by leading the SECURE framework. His insistence on multifaceted collaboration has already started to expand the SCO’s purview from a military security-focused framework to a more comprehensive one that encompasses technical innovation, cultural interaction, economic development, and environmental sustainability.

One of the most significant ramifications of Modi’s approach is that the SCO’s identity will shift from a primarily security-oriented organization to a more balanced and versatile one. With India encouraging innovation through startup forums and digital inclusion, SCO members are encouraged to look for new opportunities for economic growth and youth empowerment, moving beyond the old state-centric security paradigm. Regional collaboration in traditional medicine, the preservation and promotion of Buddhist legacy, increasing cultural and youth exchanges, and a renewed emphasis on education and interpersonal contact all contribute to this transition. The end effect is a more dynamic and integrated Eurasian society, where soft power measures supplement hard security aims, paving the road for greater mutual trust and sustained growth. [28]

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INDIA

COUNTER TERRORISM AND SECURITY COOPERATION

One of the most critical opportunities is to strengthen counterterrorism cooperation. The SCO’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS) provides India with essential intelligence-sharing and collaborative operational capabilities. The research states that “India’s participation in RATS has enabled it to plug into the wider Eurasian counter-terrorism network, thereby strengthening its capacity to anticipate and neutralize cross-border threats”.[29]

This platform enables India to address its long-standing concerns about state-sponsored terrorism in Pakistan and radical spillovers from Afghanistan within a multilateral context.

Disrupting terrorist networks in and around Afghanistan is a critical strategic task that both India and the SCO are interested in. India is a significant contributor to Afghanistan’s aid and rehabilitation efforts. A special working group on Afghanistan has also been established by the SCO, and SCO member states are actively engaged in the country’s development of roads, power, and other energy-related initiatives. This area of agreement may present SCO and India with a favorable chance to establish shared strategies and discuss solutions to issues like drug trafficking, terrorism, and the Taliban’s comeback.[30]

ENERGY AND CONNECTIVITY GAIN

India also receives institutional support from the SCO to meet its energy and connectivity requirements. India’s expanding economy depends on the hydrocarbons of Central Asia, and the SCO framework enables organized collaboration. India’s admission into the SCO “occurred with renewed discussions on energy cooperation, positioning New Delhi as a credible partner in diversifying regional energy flows,” according to the report.[31] Under the SCO umbrella, connectivity initiatives like the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and investments in Chabahar port, in addition to energy, receive more regional legitimacy.

Increasing contact in SCO with Russia and Kazakhstan, two significant global energy producers outside OPEC, could help India achieve energy security.[32]

DIPLOMATIC LEVERAGE AND MULTIPOLARITY

India’s membership in the SCO enables it to diplomatically counteract China’s or Russia’s overbearing domination in Eurasia. The paper makes clear that “India’s constructive engagement is welcomed by the Central Asian republics, who see New Delhi as a benign actor compared to the overbearing influence of Moscow and Beijing”.[33] This establishes India as a crucial pole in a multipolar order, enhancing its reputation as a stabilizing and respectable regional force.

TECHNOLOGY AND GOVERNANCE

Looking ahead, India has the potential to grow its impact in specific sectors such as digital governance and fintech. The research makes the case that “India’s digital initiatives, including its fintech and e-governance models, could serve as templates for Central Asian republics seeking modernization support”.[34] By exploiting its technological resources, India may strengthen its soft power while simultaneously establishing new types of collaboration inside the SCO.

CHALLENGES FOR INDIA

PAKISTAN FACTOR AND INSTITUTIONAL PARALYSIS

A major challenge remains Pakistan’s disruptive presence in the SCO. Despite giving New Delhi a place to voice worries about terrorism, “the India-Pakistan rivalry occasionally paralyzes the SCO’s consensus-driven mechanisms, limiting New Delhi’s ability to push ambitious initiatives.” This dynamic threatens to dilute India’s goal, particularly when Pakistan employs obstructionist measures.

RUSSIA-CHINA DOMINANCE

The SCO is still controlled by China and Russia, whose strategic interests frequently take precedence over others’, notwithstanding India’s rising prominence. “China and Russia retain the ability to block initiatives that do not serve their interests,” the report cautions. This implies that if India’s plans for energy diversification or connection clash with those of Beijing or Moscow, they may encounter resistance.

GEOGRAPHIC CONSTRAINTS AND BRI DISAGREEMENTS

Geography also restricts India’s reach. Without direct land access to Central Asia, New Delhi must rely on third-country transit routes via Iran or the INSTC. Any disruptions to these channels reduce India’s presence in Eurasia. Furthermore, India’s objection to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) confines it to the SCO’s economic objective. This research warns that “India’s cautious approach towards the BRI isolates it within the SCO’s economic agenda, where China continues to set the terms”. This structural restriction limits India’s ability to shape large-scale connectivity debates.

CONCLUSION

India’s participation in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) has gradually changed from serving as a token of its outreach to the Eurasian region to becoming a useful tool for furthering its strategic objectives. India has used the SCO over the years to improve connectivity initiatives, energy security, counterterrorism collaboration, and diplomatic relations with the Central Asian Republics (CARs). India has strengthened its national security infrastructure against terrorism and extremism by gaining access to intelligence networks throughout Eurasia through programs under the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS).

Economically, India’s membership has created prospects for energy diplomacy and trade corridors. Central Asia, with proven reserves of over 33 billion barrels of oil and over 350 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, is critical to India’s long-term energy diversification (BP Statistical Review, 2021). India’s efforts to connect via the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and investments in Chabahar port are consistent with the SCO’s economic strategy, notwithstanding its refusal to support the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which generates structural divergence.

The SCO provides India with a diplomatic platform to counterbalance China’s and Russia’s increasing hegemony in Eurasia. India is increasingly seen as a benign and stabilizing partner by the Central Asian Republics, many of which are looking for alternatives to their over-reliance on Beijing or Moscow (Aris, 2009). This impression is further reinforced by India’s democratic credentials and emphasis on developmental cooperation.

However, there are still major obstacles to overcome. Pakistan’s membership in the SCO frequently causes problems, especially when terrorism is brought up. Similarly, India’s capacity to advance bold ideas is constrained by China’s hegemony within the group and the consensus-based decision-making process. India’s expansion is further limited by its geographic location, since it depends on precarious routes through Iran and Afghanistan in lieu of direct borders with Central Asia. This vulnerability was shown by the fall of Kabul in 2021, when the SCO itself found it difficult to develop a cohesive Afghan strategy.

Looking ahead, India’s SCO significance and future direction will be determined by its ability to effectively convert chances into actual rewards. India must increase its niche contributions in sectors where it has demonstrable comparative advantages, such as digital governance, fintech, medicines, and capacity building. Similarly, continued investments in energy diplomacy and connectivity will determine whether India can establish itself as a key Eurasian stakeholder rather than a peripheral player.

In summary, India’s strategic calculation has benefited greatly from the SCO, which has given it influence and visibility in Eurasia during a period of shifting global alignments. The ability of India to maintain regional peace, manage great-power rivalries, and increase its strategic presence in the resource-rich and geopolitically sensitive heartland of Eurasia will ultimately determine its future in the SCO.

References

[1]Sajjanhar, A. (2022). India and Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Vital Partnership. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 17(3/4), 190–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48772509

[2]Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (n.d.). General information. https://eng.sectsco.org/20170109/192193.html

[3]Ibid

[4]Kundu, N. D. (2009). Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Significance for India. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 4(3), 91–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45340804

[5]Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2015). Annual report 2014-15. https://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/25009_External_Affairs_2014-2015__English_.pdf

[6]The Economic Times. (2014, March 25). India’s membership in Shanghai Cooperation Organisation initiated. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/indias-membership-in-shanghai-cooperation-organisation-initiated/articleshow/42366325.cms?from=mdr

[7]Kumari, K. (n.d.). India in SCO: India will be of great significance to the regional security (Exclusive). Armedia. https://armedia.am/eng/print/30675/

[8]Joshi, N. (2015). The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: An assessment. Vivekananda International Foundation. https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/the-shanghai-cooperation-organization-an-assessment.pdf

[9]Mann, P. (2016). India’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Opportunities and challenges. Air Power Journal, 11(2), Pg 126. https://capsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Poonam-Mann-2.pdf

[10]Mann, P. (2016). India’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Opportunities and challenges. Air Power Journal, 11(2), Pg 141. https://capsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Poonam-Mann-2.pdf

[11]Press Information Bureau. (2022, April 3). Connectivity with the Central Asian countries remains a key priority for India: President Kovind [Press release]. PIB. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1812984

[12]Mann, P. (2016). India’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Opportunities and challenges. Air Power Journal, 11(2), Page 136. https://capsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Poonam-Mann-2.pdf

[13]Sultan, A. M. A. (2020). The importance of the Central Asian region in energy security at the global level: A review. Public Administration, 98(4), 1093–1107. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2427

[14]Sajjanhar, A. (2022). India and Shanghai Cooperation Organization: A Vital Partnership. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 17(3/4), 190–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48772509

[15]Mann, P. (2016). India’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Opportunities and challenges. Air Power Journal, 11(2), 125–142. https://capsindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Poonam-Mann-2.pdf

[16]Hindustan Times. (2018, June 10). SCO summit highlights: PM says connectivity with neighbourhood top priority. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/sco-summit-live-pm-modi-meets-xi-jinping-at-welcome-ceremony-in-china-s-qingdao/story-Xb9qGSR9ol0kXvHJxeGmzL.html

[17]Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (2020, November 30). Joint communique following the nineteenth meeting of the Council of Heads of Governments (Prime Ministers) of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization member states. https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/33249/Joint+Communique+following+the+nineteenth+meeting+of+the+Council+of+Heads+of+Governments+Prime+Ministers+of+the+Shanghai+Cooperation+Organization+Member+States

[18]Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2023, July 4). English translation of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi’s remarks at the 23rd SCO Summit. https://www.mea.gov.in/virtual-meetings-detail.htm?36750/English+Translation+of+Prime+Minister+Shri+Narendra+Modis+Remarks+at+the+23rd+SCO+Summit

[19]Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2023, July 4). New Delhi Declaration of the Council of Heads of State of Shanghai Cooperation Organization. https://www.mea.gov.in/virtual-meetings-detail.htm?36751/New+Delhi+Declaration+of+the+Council+of+Heads+of+State+of+Shanghai+Cooperation+Organization

[20]Balinder, S., Jagmeet, B., & Sandeep, S. (2023, May 20). India’s institutional inclusive engagement approach towards SCO: Takeaways from theme ‘SECURE-SCO’ – Analysis. Eurasia Review. https://www.eurasiareview.com/20230520-indias-institutional-inclusive-engagement-approach-towards-sco-takeaways-from-theme-secure-sco-analysis/

[21]CESCube. (2023). SCO Defence Ministers Meet 2023 – India’s agenda. Retrieved August 21, 2025, from https://www.cescube.com/vp-sco-defence-ministers-meet-2023-india-s-agenda

[22]Economic Times Government. (2024). Priorities at SCO Summit shaped by PM Modi’s SECURE vision, says India. Economic Times. https://government.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/policy/priorities-at-sco-summit-shaped-by-pm-modis-secure-vision-says-india/111451257

[23]Indian Council of World Affairs. (2023). Towards a secure Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Views of SCO resident researchers at ICWA. Indian Council of World Affairs. https://icwa.in/pdfs/TowardsSecureSCOWeb.pdf

[24]Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Government of India. (n.d.). Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) – Startup and innovation initiatives. Startup India. Retrieved August 21, 2025, from https://www.startupindia.gov.in/sih/en/sco.html

[25]BW Wellbeing World. (2023). 25 SCO countries come together to promote traditional medicine. https://www.bwwellbeingworld.com/article/25-sco-countries-come-together-to-promote-traditional-medicine-471086

[26]Department of Science and Technology, Government of India & Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. (2022, October 10–14). 2nd SCO-Young Scientists Conclave. https://www.frccsc.ru/sites/default/files/YOUNG%20SCIENTISTS%20CONCLAVE%202022.pdf?868

[27]Gaur, P. (2022). International Conference “Shanghai Cooperation Organization: from Central Asia to Eurasia”. Indian Council of World Affairs. https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=1&ls_id=7546&lid=5043

[28]Economic Times Government. (2024). Priorities at SCO Summit shaped by PM Modi’s SECURE vision, says India. Economic Times. https://government.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/policy/priorities-at-sco-summit-shaped-by-pm-modis-secure-vision-says-india/111451257

[29]Indian Council of World Affairs. (2023). Towards a secure Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Views of SCO resident researchers. Indian Council of World Affairs. https://icwa.in/pdfs/TowardsSecureSCOWeb.pdf

[30]Kundu, N. D. (2009). Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Significance for India. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 4(3), 91–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45340804

[31]Indian Council of World Affairs. (2023). Towards a secure Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Views of SCO resident researchers. Indian Council of World Affairs. https://icwa.in/pdfs/TowardsSecureSCOWeb.pdf

[32]Kundu, N. D. (2009). Shanghai Cooperation Organisation: Significance for India. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 4(3), 91–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45340804

[33]Indian Council of World Affairs. (2023). Towards a secure Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Views of SCO resident researchers. Indian Council of World Affairs. https://icwa.in/pdfs/TowardsSecureSCOWeb.pdf

[34]Ibid