The conduct of elections in India is constitutionally entrusted to the Election Commission of India (ECI) under Article 324 of the Constitution. This power, described as plenary in form, has nonetheless been repeatedly characterised by the Supreme Court as fiduciary, structured, and subject to constitutional discipline.

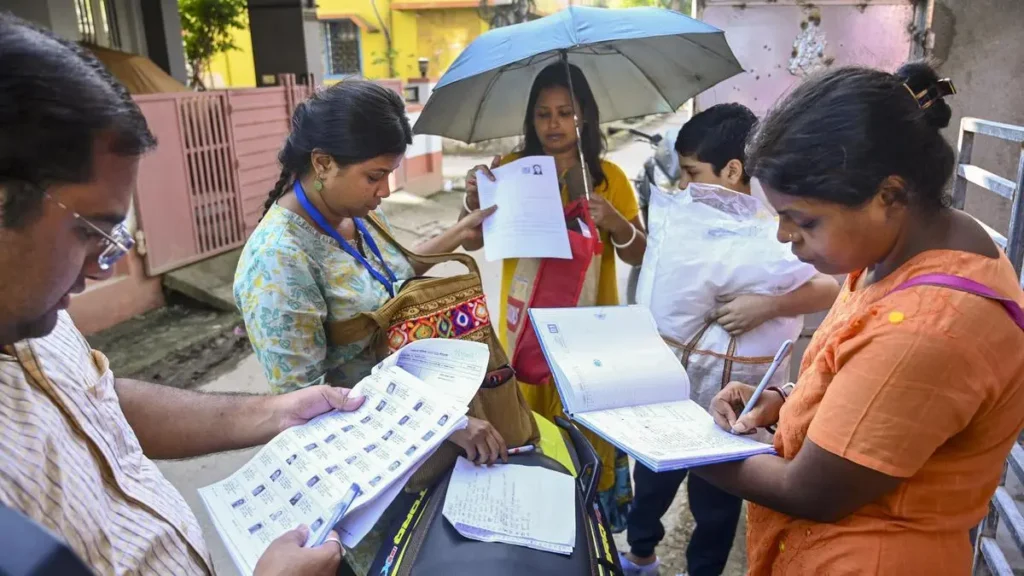

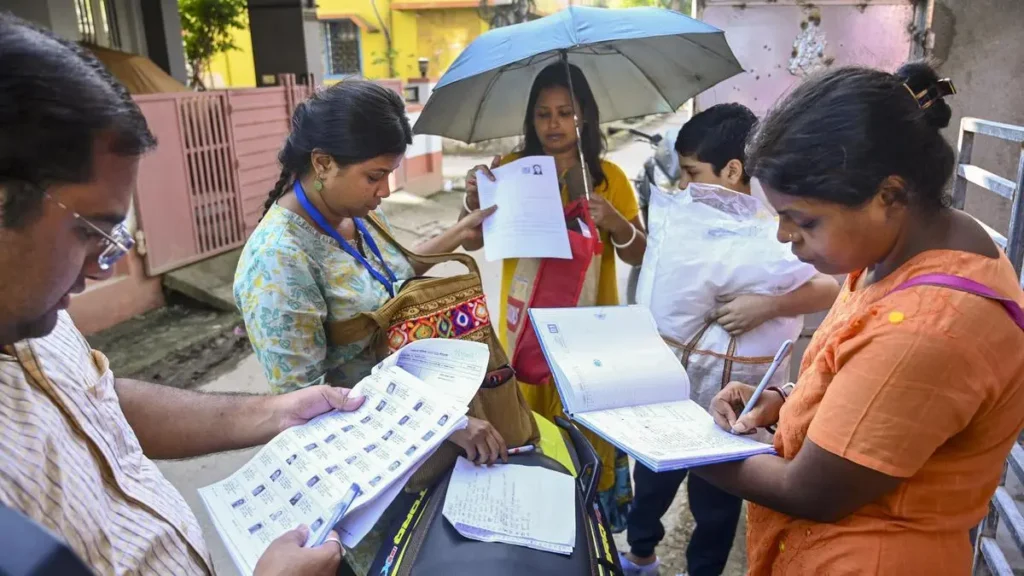

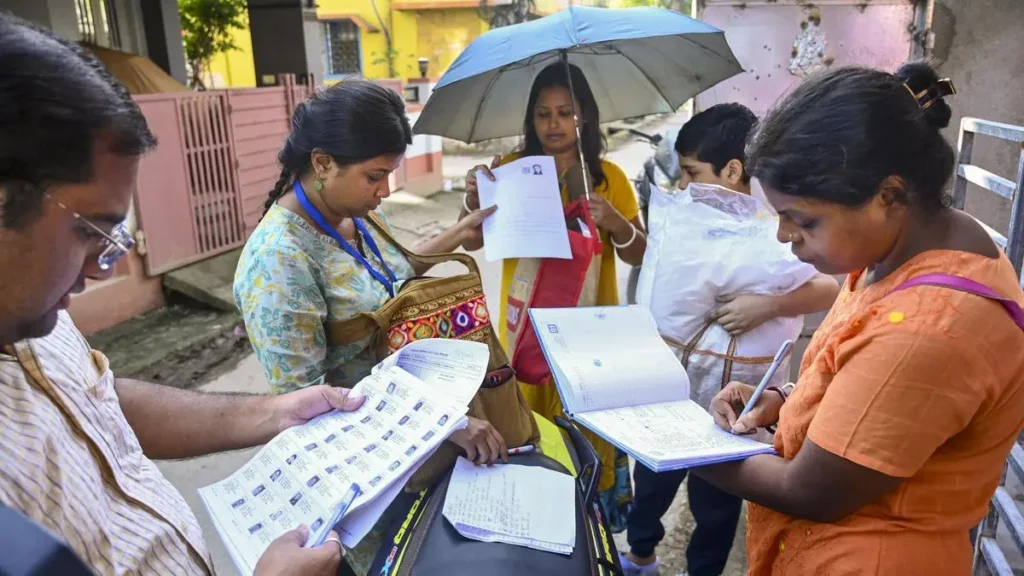

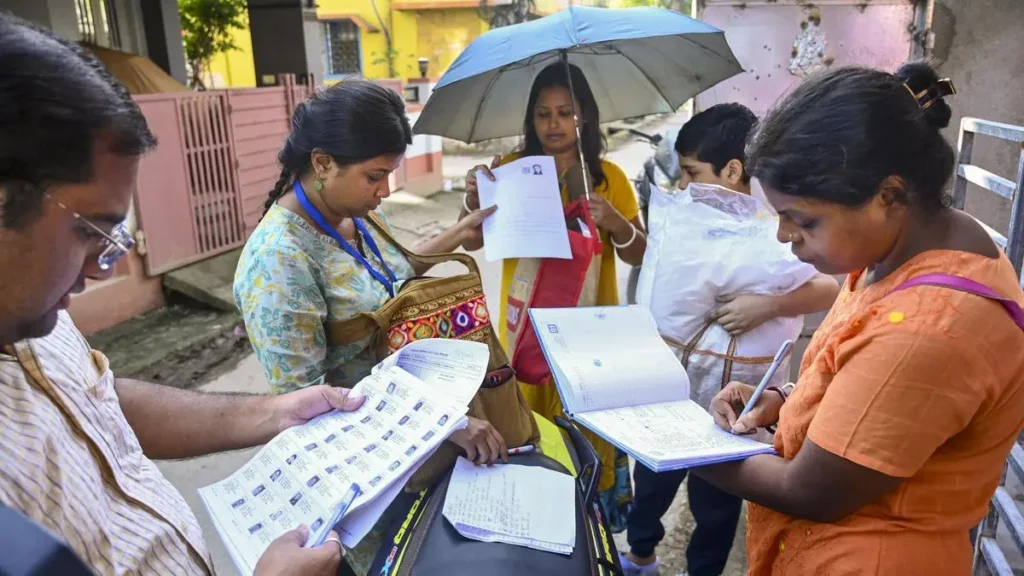

Recent investigative findings published by The Reporters’ Collective (February 8, 2026) concerning the ECI’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in West Bengal raise foundational questions about the conversion of procedural authority into substantive control, and about the judiciary’s role when credible material suggests systemic deviation from statutory and constitutional norms.

The central issue is not whether the ECI may revise electoral rolls, which is beyond dispute, but whether the manner of exercise has crossed the line from regulation into domination, thereby imperilling the franchise itself. At stake is not merely administrative irregularity, but the architecture of electoral constitutionalism.

Statutory architecture and its subversion

Under the Representation of the People Act, 1950, Electoral Registration Officers (ERO) are the statutory authorities vested with quasi-judicial power to determine inclusion or deletion of names in electoral rolls. Sections 22 and 23 confer decision-making authority on the ERO based on their “satisfaction,” following due inquiry.

The investigation alleges that during the West Bengal SIR, EROs were systematically stripped of decisional autonomy, reduced to intermediaries tasked with document collection, while substantive determinations were escalated to “Electoral Roll Observers” and centralised supervisory layers lacking statutory provenance.

This alleged hollowing-out of statutory office squarely implicates the principle articulated in AK Roy v Union of India, where the Supreme Court held: “When a statute vests power in a designated authority, that power must be exercised by that authority alone and by no other.”

Similarly, in State of Punjab v Hari Kishan Sharma, the top court warned against “administrative superstructures” displacing statutory decision makers, holding that such practices are ultra vires.

If the findings are accurate, the SIR represents not mere supervision but institutional displacement, rendering the statutory scheme functionally inoperative.

Informality and erosion of procedural process

A striking feature of the reported exercise is governance through informal, non-public channels like WhatsApp instructions, oral directions in video conferences and evolving criteria not anchored in any publicly notified manual.

The Supreme Court has consistently held that procedural fairness is not optional where civil consequences ensue, and that State action affecting rights must be traceable to known, stable norms.

In State of Punjab v Gurdev Singh, the Supreme Court held: “An order which has civil consequences must be made consistently with the rules of natural justice.”

More pointedly, in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India, the apex court expanded Article 21 to require that any procedure affecting rights be “right, just and fair, and not arbitrary, fanciful or oppressive.”

A rolling, opaque decision-making process in which the criteria for suspicion change mid-exercise fails this test. It substitutes administrative convenience for constitutional legality.

Algorithmic decision-making and constitutional accountability

The reported use of ERONET 2.0, including real-time toggling of functionalities and algorithmic flagging of “logical discrepancies,” raises concerns about delegation to unverified technological systems.

The Supreme Court has cautioned that automation does not dilute constitutional responsibility. In Anuradha Bhasin v Union of India, the court held: “Executive action cannot be immune from judicial scrutiny merely because it is based on technical or technological considerations.”

Further, in KS Puttaswamy v Union of India, the court emphasised that systems that profile or classify individuals must satisfy the requirements of legality, necessity and proportionality.

An unaudited algorithm that expands “suspicious voters” from 32 lakh to 1.5 crore on the basis of spelling variations or digitisation artefacts fails every limb of this test. Technology here appears not as an aid to statutory judgment, but as a substitute for it.

Disparate impact: When neutral filters produce Unequal outcomes

Perhaps the gravest constitutional implication arises from the reported disproportionate flagging of Muslim voters in constituencies such as Bhabanipur. Even absent explicit intent, a measure that produces systematic, group-specific disadvantage, attracts Article 14 scrutiny.

In EP Royappa v State of Tamil Nadu, the Supreme Court famously held: “Equality is antithetic to arbitrariness.”

More recently, in Navtej Singh Johar v Union of India, the top court recognised that constitutional injury may arise from disparate impact, not merely express classification.

If algorithmic or procedural filters disproportionately burden a religious minority, especially in the domain of the franchise, which is the foundation of democratic citizenship, the action demands the strictest judicial scrutiny.

Article 324: Discretion vs dominion

The ECI’s reported argument before the Supreme Court that it may conduct revisions “as it may deem fit” is constitutionally untenable if read literally.

In Mohinder Singh Gill v Chief Election Commissioner, the Supreme Court made clear: “Article 324 is meant to supplement, not supplant, the law.” Similarly, in Election Commission of India v Ashok Kumar, the court cautioned, “Plenary powers are not absolute powers.”

The transformation of the ECI from a custodian of the roll into its master, empowered to redefine standards mid-stream without transparency or review, marks a constitutional regression.

Judicial notice, suo motu review based on independent investigations

This brings us to the final and unavoidable question: What is the judiciary’s obligation when credible, detailed investigative material reveals systemic risk to electoral rights?

Indian constitutional practice recognises that courts may act suo motu where matters of grave public importance arise. In Vineet Narain v Union of India, the Supreme Court held: “Where institutions charged with the duty of accountability fail, judicial intervention becomes inevitable.”

High Courts have similarly taken cognisance of investigative journalism where it disclosed prima facie violations of fundamental rights, particularly where affected populations lack effective access to remedies.

The question is therefore not whether such reports are conclusive, but whether they are sufficient to trigger judicial scrutiny, monitoring and demand for institutional explanation. In a constitutional democracy, the answer must be in the affirmative.

The judiciary at the crossroads of democracy

If the findings reported by The Reporters’ Collective are even substantially accurate, they disclose an electoral exercise that is procedurally unstable, technologically opaque and constitutionally asymmetrical in impact. Such an exercise cannot be insulated by incantations of administrative expertise or constitutional status.

The greater danger lies in normalisation. An unreviewed precedent of “revision by flux” risks recalibrating the relationship between citizen and State, transforming the franchise from a presumptive right into a conditionally renewable privilege.

At this juncture, constitutional fidelity demands that courts ask not merely whether the ECI acted within jurisdiction, but whether the manner of action preserved the democratic compact itself.

Where credible material suggests otherwise, judicial notice, suo motu oversight and, if necessary, declaration of invalidity are not acts of overreach. They are acts of constitutional preservation.

Jai Hind.