In the wee hours of Saturday (3rd January), Caracas woke up to the sound of fighter jets slicing through the night sky. By morning, it was clear that Venezuela had become the latest stage for a familiar American drama, one where military force is framed as a moral mission to “restore democracy.”

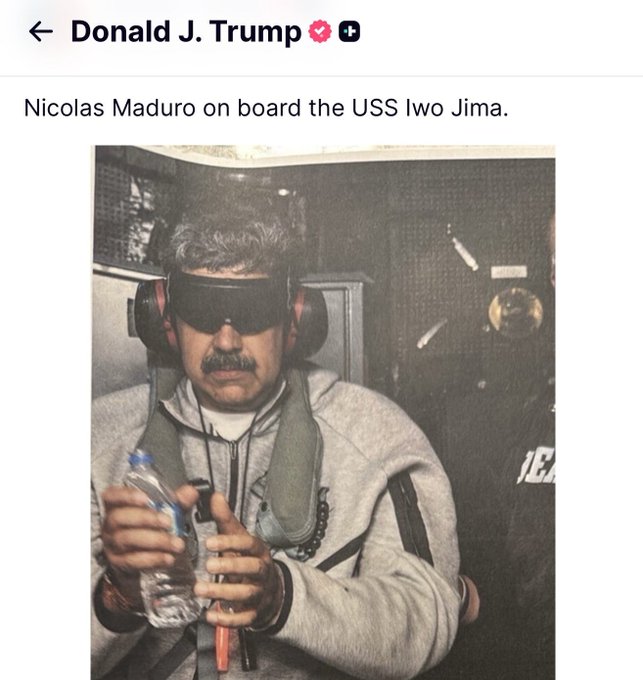

US President Donald Trump confirmed that American forces had carried out multiple strikes in Venezuela and captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, flying them to the United States. Trump announced the operation on Truth Social, presenting it as a decisive blow against what he called “narcotic terrorism.”

Soon after, US Attorney General Pamela Bondi revealed that Maduro and Flores had been indicted in New York on charges ranging from narco-terrorism conspiracy to cocaine importation and possession of heavy weapons.

Trump accused the Maduro government of pushing migrants toward the US southern border, emptying prisons and mental institutions, and collaborating with drug cartels and terrorist groups. According to Trump, Venezuela had become a major transit route for cocaine entering the United States, with boats smuggling narcotics through the Caribbean and the Pacific.

The justification sounded familiar. It has been for many years that Washington has branded hostile regimes as being guilty of crime, human rights abuses, or threatening international security.

In the Venezuelan instance, matters were heightened by the Trump administration’s military campaign against reported drug-carrying boats in September of 2025 as it launched “a new war on drugs.” This is taking on military rather than law enforcement efforts.

However, Maduro had always denied such charges, terming them a cover for the eventual control of Venezuela’s huge oil reserves. Notably, just days before the strikes, Maduro had offered cooperation with the US on migration and drug trafficking. That offer was ignored. Instead, American jets flew in without congressional approval, raising serious constitutional questions back home..

What unfolded in Venezuela fits a pattern the world has seen many times before, a regime change operation wrapped in the language of democracy, security, and moral responsibility.

Regime change in the name of restoring democracy

The US intervention in Venezuela did not emerge in a vacuum. It is part of a long and deeply troubling history of American-led regime change across the world. From Vietnam to Iraq, from Afghanistan to Syria, Washington has repeatedly justified military action as a way to remove “bad regimes” and replace them with democratic systems. The results, more often than not, have been chaos, violence, and long-term instability.

In late 2001, US-backed forces entered Kabul, toppling the Taliban government within weeks. Hamid Karzai was installed as Afghanistan’s leader with strong American backing, and President George W. Bush confidently spoke of democracy taking root in Central Asia. Two decades later, US troops withdrew, and the Taliban returned to power almost overnight. The American-installed government collapsed with shocking speed, exposing how hollow and dependent it had always been.

Iraq followed a similar path. In 2003, US troops removed Saddam Hussein, promising to transform Iraq into a democratic beacon for the Middle East. Instead, the dismantling of Iraq’s security apparatus left hundreds of thousands of armed men unemployed. The country descended into insurgency, sectarian violence, and civil war. Iran-backed militias gained influence, and the chaos eventually gave rise to the Islamic State, reshaping the region’s security landscape in ways that continue to haunt it today.

— Censored Humans (@CensoredHumans) January 3, 2026

Iraq December 2003: Saddam Hussein captured by the United States.

Venezuela January 2026: Nicolás Maduro captured by the same power

When the United States can’t control a nation, it criminalizes its leader. pic.twitter.com/xWTV6lwcBq

Syria, Libya, and earlier Vietnam tell variations of the same story. The US steps in claiming moral urgency, dismantles existing power structures, and leaves behind fractured societies. Scholars describe this pattern as foreign-imposed regime change.

Over the past 120 years, the United States has been responsible for the forced removal of around 35 foreign leaders, nearly one-third of all such interventions globally. Alarmingly, about one-third of these regime changes are followed by civil war within a decade.

Even Trump, who built his political appeal on opposing America’s “endless wars,” seems unable to break free from this tradition. While he has repeatedly condemned the Iraq invasion and criticised neoconservative foreign policy, his Venezuela intervention sits uneasily with his own rhetoric of being a “peace President.”

Bangladesh: A regime change backed by US without bombs

While Venezuela saw fighter jets and missiles, Bangladesh offers a more subtle example of American interference, one carried out through political pressure, intelligence networks, and street protests rather than direct military force.

According to a book, Inshallah Bangladesh: The Story of an Unfinished Revolution, Sheikh Hasina’s former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal has accused the CIA of orchestrating her removal from power. He described the events as a “perfect CIA plot,” carefully planned over time and executed with the help of Bangladesh’s own military leadership.

Kamal claimed that the country’s army chief, General Waker-Uz-Zaman, was central to the conspiracy. Shockingly, he said that even Bangladesh’s top intelligence agencies failed to warn Hasina, suggesting that senior officials may have been compromised. According to Kamal, Waker forced Hasina to leave the country on 5th August, 2024, just weeks after taking over as army chief, a position to which Hasina herself had appointed him.

The protests that preceded Hasina’s fall were portrayed internationally as so called student-led and democratic. But Kamal said that radical Islamist groups like Jamaat-e-Islami, historically divided, united for the first time with backing from foreign intelligence networks. He further claimed that Pakistan’s ISI played a role, with foreign-trained militants mixing with protesters and attacking police.

The motivation, Kamal argued, was strategic. Washington, he said, does not want too many strong leaders in South Asia at the same time. With Narendra Modi in India and Xi Jinping in China, Hasina’s independent stance made her inconvenient. Another key factor was St Martin’s Island in the Bay of Bengal, a strategically located territory near Myanmar and critical to Indian Ocean geopolitics.

Hasina herself had publicly stated that the US pressured her to hand over access to the island in exchange for staying in power. She refused, calling it a violation of Bangladesh’s sovereignty. After her removal, economist Muhammad Yunus, unelected and widely seen as Western-friendly, was installed at the helm, raising serious questions about democratic legitimacy.

Friends with dictators, enemies of Democracy

What makes America’s democracy narrative even more troubling is its close and comfortable relationship with authoritarian regimes, provided they align with US strategic interests. Saudi Arabia stands out as one of the clearest examples.

The kingdom has no elections, no political parties, and no meaningful political freedoms. Yet Washington continues to treat it as a key ally.

Recently, the US cleared $1.4 billion in military sales to Saudi Arabia, including hundreds of millions for training its land forces. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s visit to the White House resulted in authorisation for F-35 fighter jet sales and a Strategic Defense Agreement that firmly re-established the US as Saudi Arabia’s main security guarantor.

This is the same Saudi leadership that has faced global outrage over human rights abuses, the war in Yemen, and the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Yet none of this seems to disqualify Riyadh from American support.

Beyond Saudi Arabia, the US maintains strong ties with other authoritarian states across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Egypt, ruled by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi after a military coup, receives billions in US military aid.

The United Arab Emirates, an absolute monarchy, is another close partner of US. These relationships are rarely framed as problems for democracy. Instead, they are justified in the language of “stability,” “security,” and “regional balance.”

Even when these regimes suppress dissent or jail opponents, Washington looks the other way, so long as military bases, arms deals, and strategic cooperation remain intact.

The hypocrisy at the heart of American power

When viewed together, Venezuela, Afghanistan, Iraq, Bangladesh, and America’s alliances with authoritarian regimes reveal a deep and enduring hypocrisy. Democracy is invoked selectively, used as a weapon against adversaries and quietly ignored when dealing with friends.

Governments that resist US influence are branded criminal, illegitimate, or dangerous. Those that comply, even if they rule without elections or suppress basic freedoms, are rewarded with weapons, diplomatic cover, and political legitimacy.

The pattern is hard to ignore. Regime change is not about democracy; it is about control. It is about oil, military bases, shipping routes, and geopolitical leverage. From Latin America to South Asia, the United States has repeatedly shown that its commitment is not to democratic values, but to strategic advantage.

Venezuela’s latest crisis is not an exception, it is the continuation of a long tradition. And until this contradiction is honestly confronted, the promise of democracy offered by American power will remain, for much of the world, deeply unconvincing.